19th century sources

website of Jelle Verheij, historian

home | publications | pictures | historical pictures | travel snap shots | monuments | 19th century sources | research tools | links | contact

Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh May and June 1898

(by J.H. Monahan, British Vice-Consul in Bitlis)

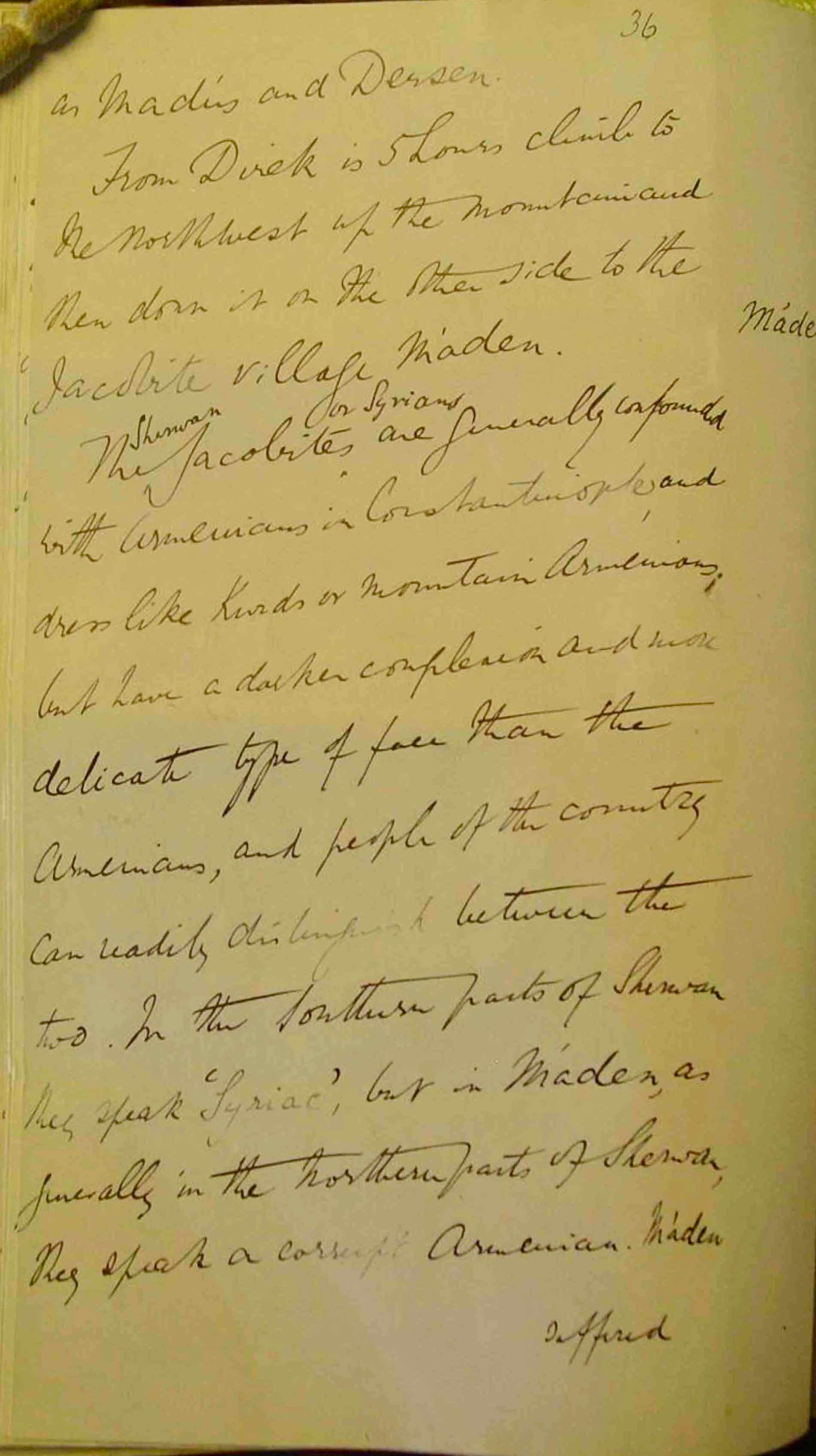

[174v] as Med’us and Dersen.

From Direk is 5 hours climb to the Northwest of the mountain and then down it on the other side to the Jacobite village Maden.

The Sherwan Jacobites or Syrians are generally confused with Armenians in Constantinople, and dress like Kurds or mountain Armenians, but have a darker complexion and more delicate type of face than the Armenians, and people of the country can easily distinguish between the two. In the southern parts of Sherwan they speak ‘Syriac’, but in Maden, as generally in the northern part of Sherwan, they speak a corrupt Armenian. Maden

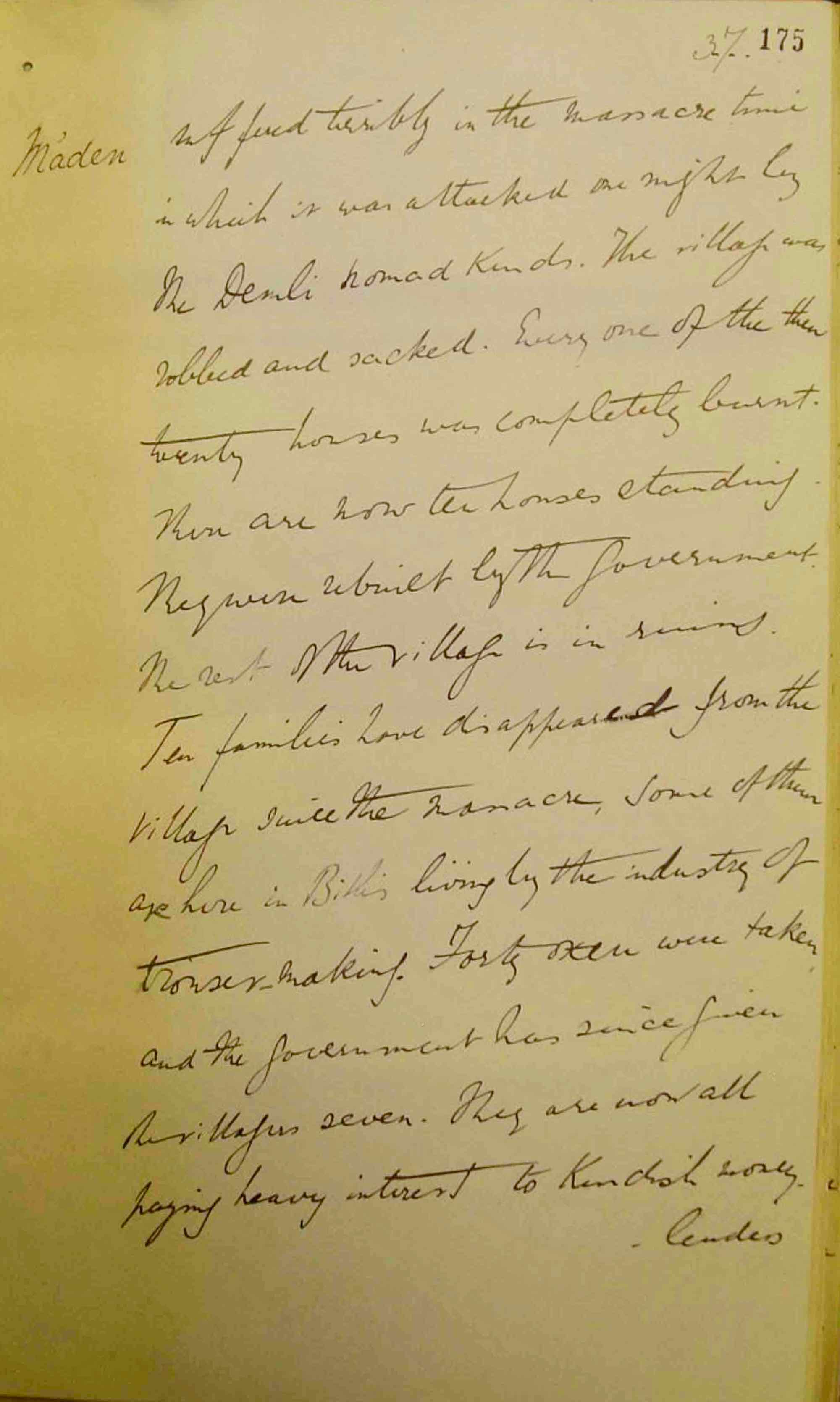

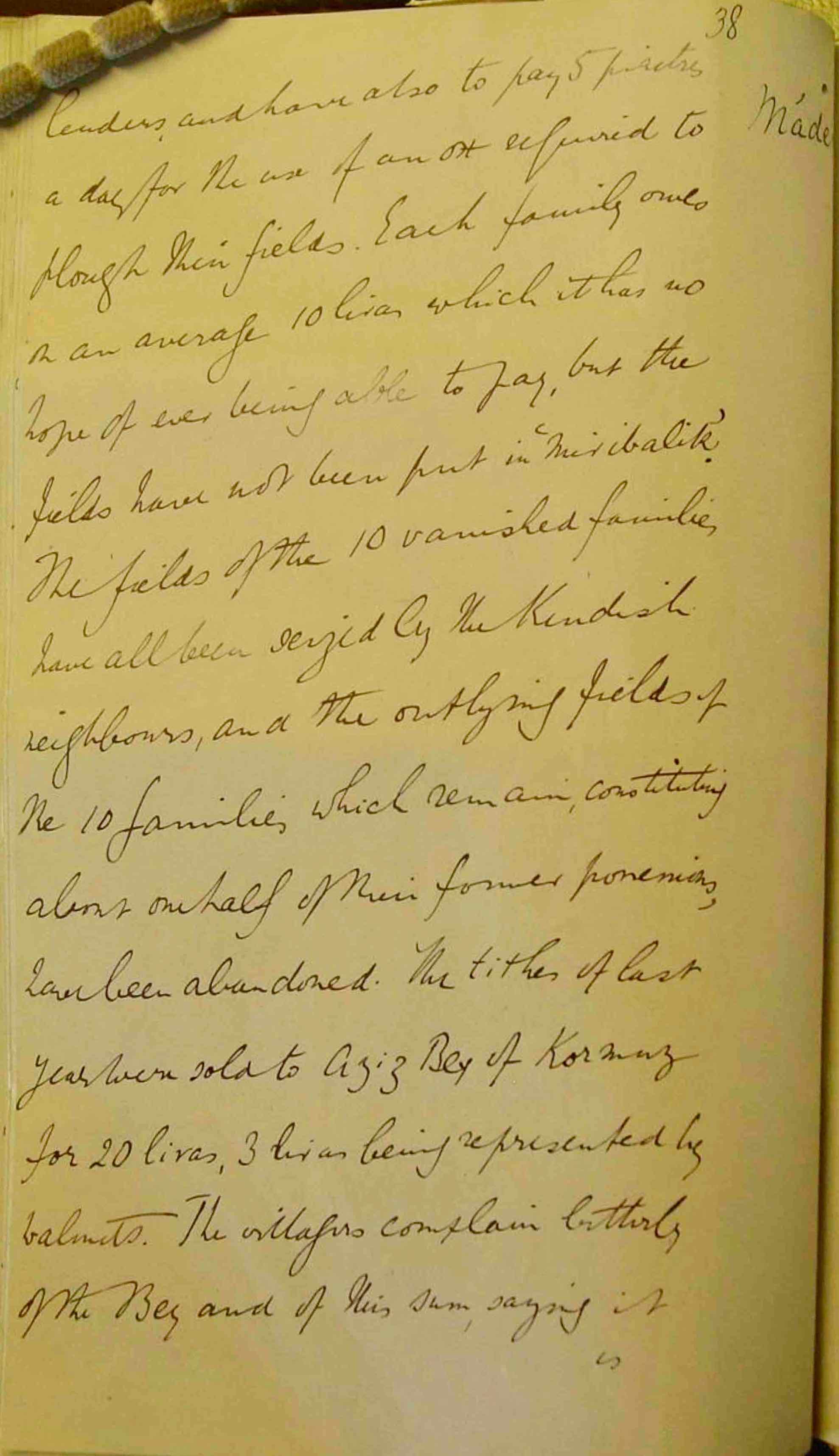

[175v] lenders and have also to pay 5 piasters a day for the use of an ox employed? to plough their fields. Each family owes on an average 10 liras, which it has no hope of ever being able to pay, but the fields have not been put in “miribalik”. The fields of the 10 vanished families have all been seized by the Kurdish neighbours, and the outlying fields of the 10 families which remain, about one half of their former possessions, have been abandoned. The tithes of last year were sold to Aziz Bey of Kormuz for 20 liras, 3 liras being represented by walnuts. The villagers complain bitterly of the Bey and of this sum, saying it

[175] suffered terribly in the massacre time in which it was attacked one night by the Demli nomad Kurds. The village was robbed and sacked. Everyone of the then twenty houses were completely burnt. There are now ten houses standing. They were rebuilt by the Government. The rest of the village is in ruins. Ten families have disappeared from the village since the massacre, some of the are here in Bitlis living by the industry of trouser making. Forty oxen were taken and the government has since given the villagers seven. They are now paying all heavy interest to Kurdish money

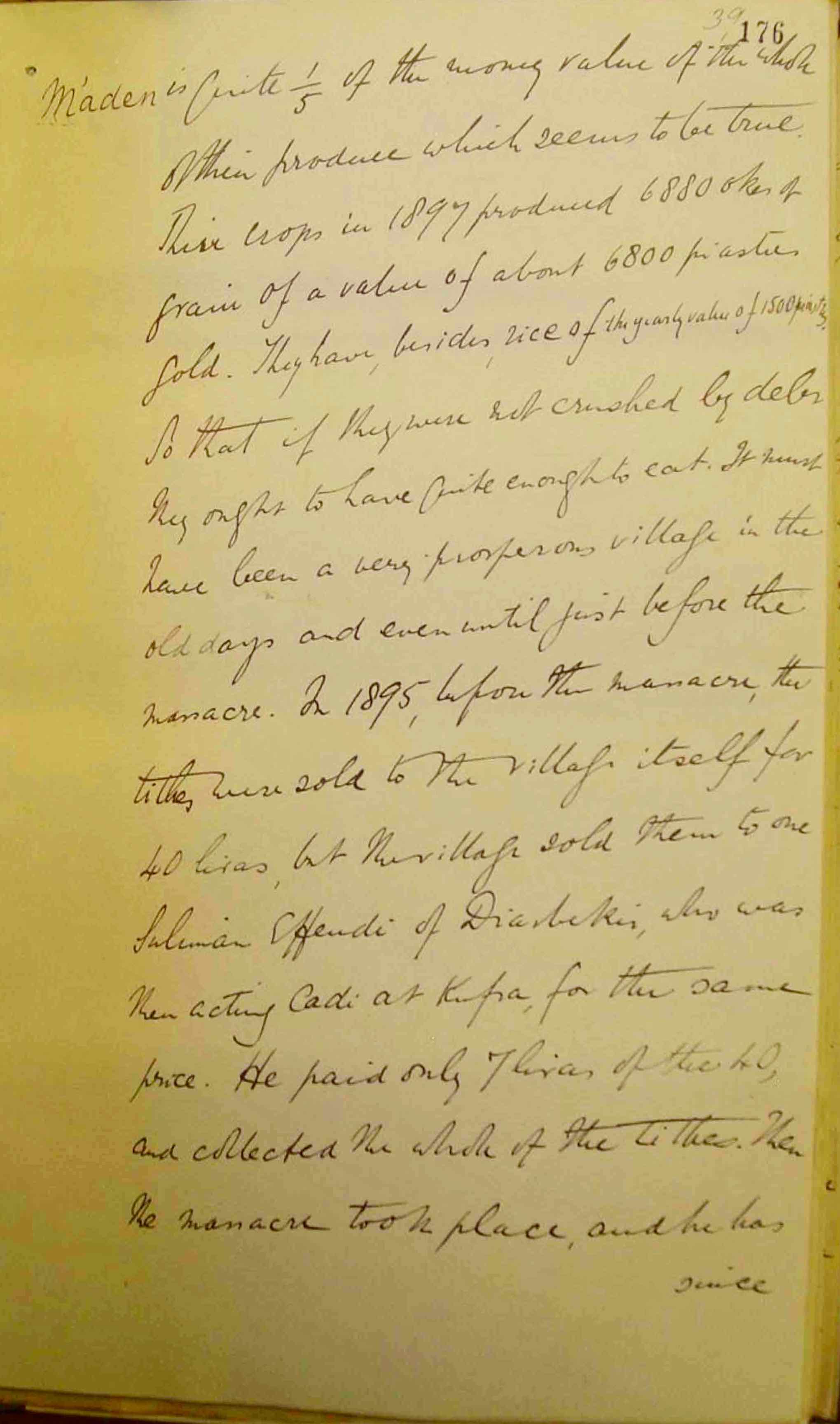

[176] is quite 1/5 of the money value of the … … of their produce which seems to be true. Their crops in 1897 produced 6,880 okes of grain of a value of about 6,800 piasters gold. They have besides rice of the yearly value of 1,500 piasters. So that if they were not crushed by debt they ought to have quite enough to eat. It must have been a very prosperous village in the old days and even until just before the massacre. In 1895, before the massacre, their tithes were sold to the village itself for 40 liras, but their village sold them to one Suleiman Effendi of Diarbekir, who was then acting Cadi at Kufra, for the same price. He paid only 7 liras of the 40, and collected the whole of the tithes. Then the massacre took place en has

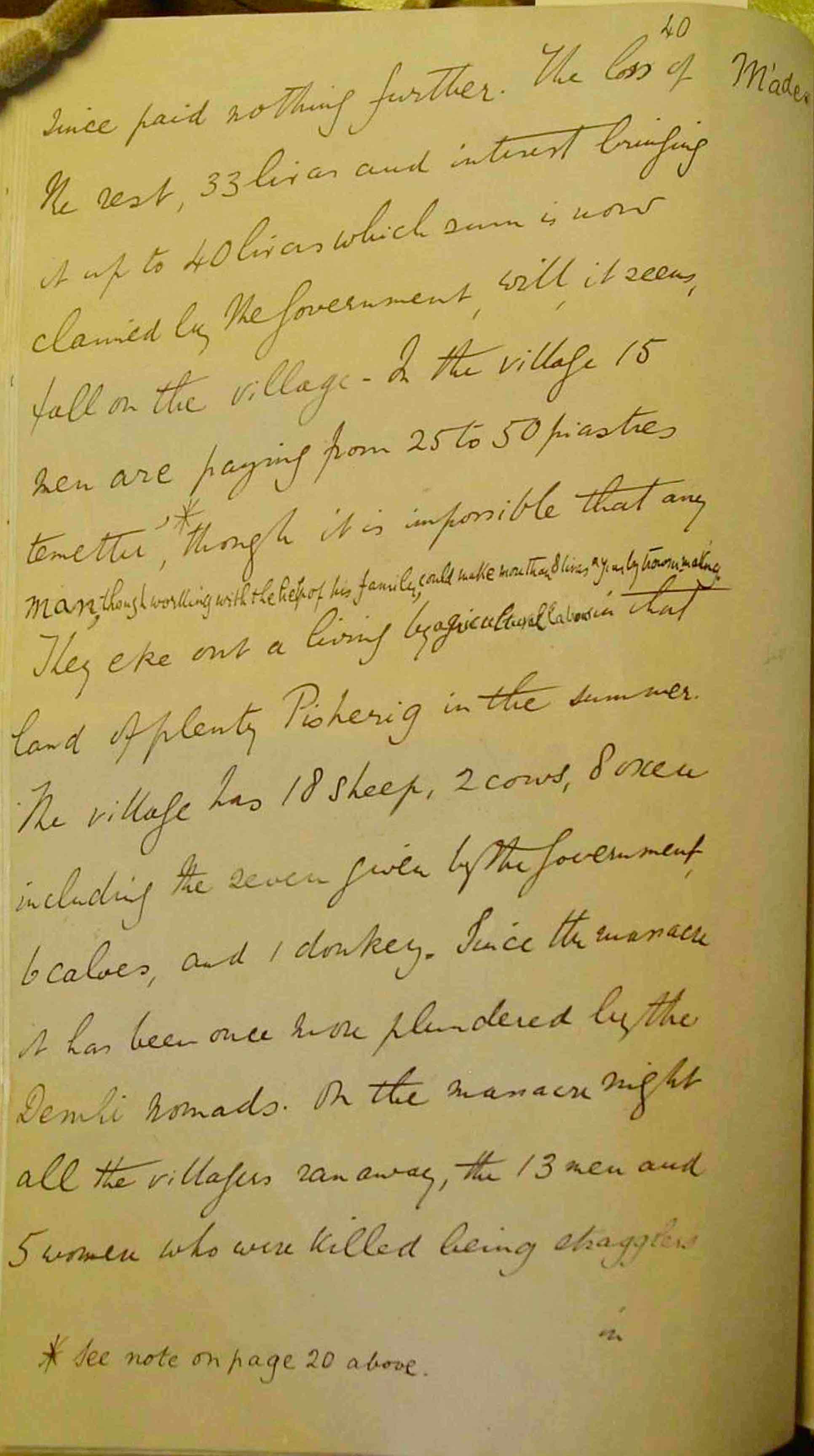

[176v] since paid nothing further. The loss of the rest, 33 liras and interest bringing it up to 40 liras which sum is now claimed by the government, will, it seems, fall on the village. In the village 15 men are paying from 25 to 50 piasters temettu’, though it is impossibleble that any man, though working with the help of his family, could make more than 8 liras a year by … making? They eke out a living by agricultural labour? that land of plenty Piskerig in the summer [unclear sentence].

The village gas 18 sheep, 2 cows, 8 oxen including the seven given by the government, 6 calves and 1 donkey. Since the massacre it has been once more plundered by the Demli nomads. On the massacre night all the villagers ran away, the 13 men and 5 women who were killed being stragglers

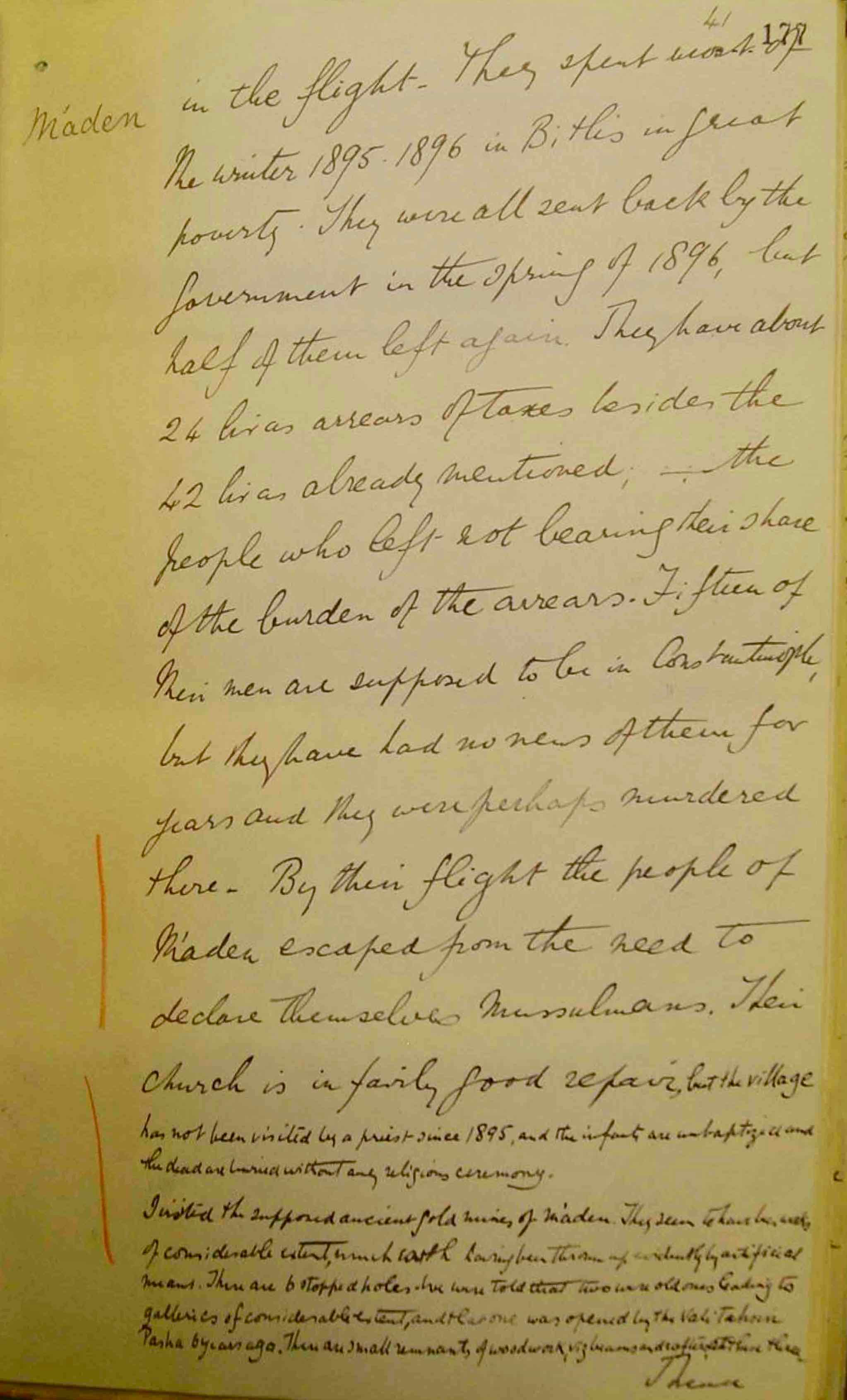

[177] in the flight. They spent most of the winter 1895 - 1896 in Bitlis in great poverty. They were all sent back by the Government in the Spring of 1896, but half of them left again. They have about 24 liras arrears of taxes besides the 42 liras already mentioned. The people who left not bearing their share of the burden of the arrears. 7 or ten of their men are supposed to be in Constantinople, but they have no news of them for years and they were perhaps murdered there. By their flight the people of Maden escaped from the need to declare themselves Mussulmans. Their church is in fairly good repair, but the village has not been visited by a priest since 1895 and the infants are unbaptised and the dead are buried without any religious ceremony.

I visited the supposed ancient gold mines of Maden. They seem to gave be .. of considerable extent, much earth having been thrown up …. by artificial means. There are 6 stopped holes. We were tied that two were old ones and leading to galleries of formidable extent, and that one was opened by the Vali Tahsin Pasha 6 years ago. There are small remnants of wood work, …………. [unreadable textı]

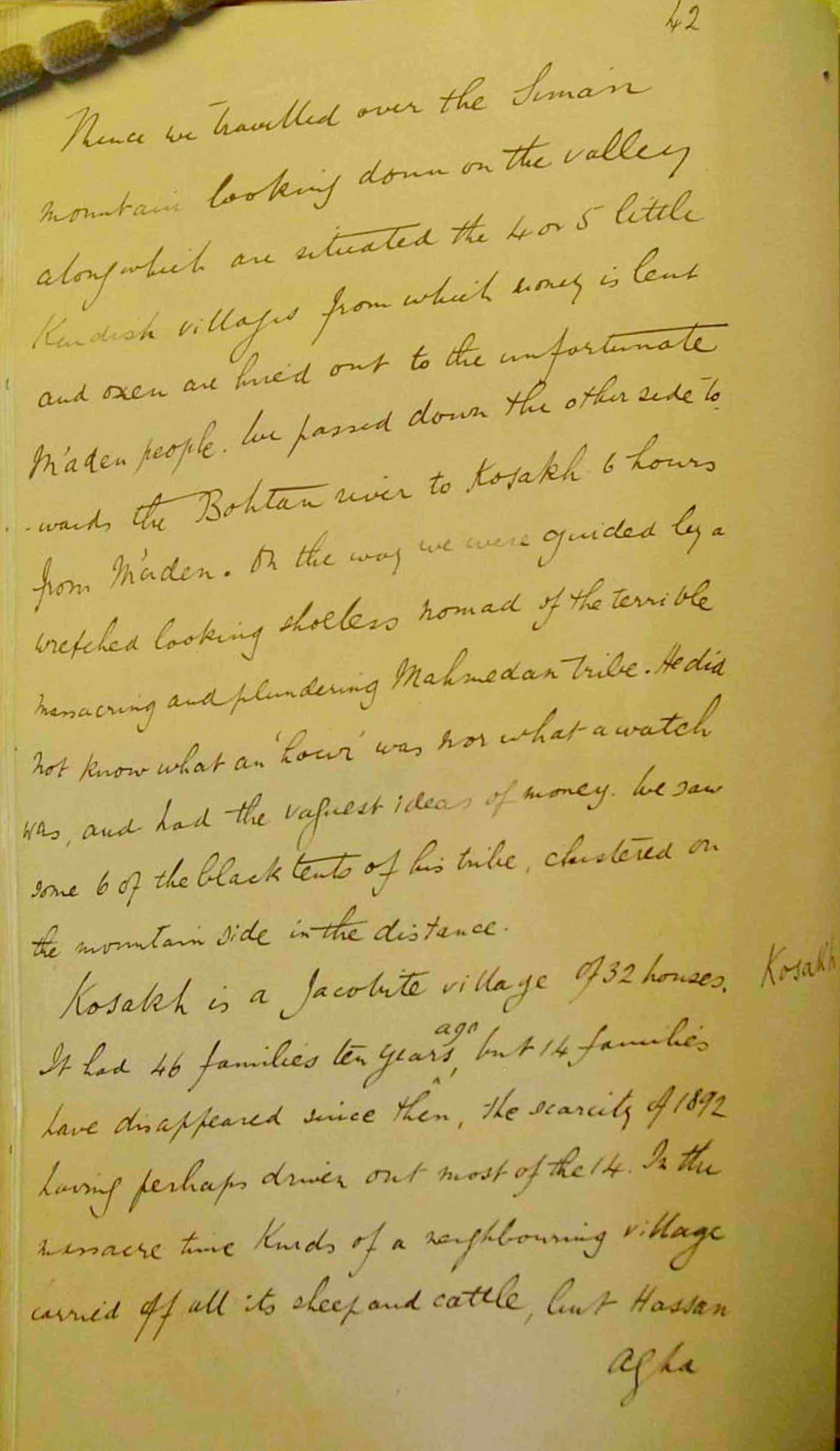

[177v] since we travelled over the Simair? mountain looking down on the valley along which are situated 4 or 5 little Kurdish villages from which money is lent and and owed are hired out to the unfortunate M’aden people. We passed down to the other side towards the Bohtan River to Kosakh 6 hours from M’aden. On the way we were guided by a wretched looking shoeless nomad of the terrible massacring and plundering Mahmedan tribe. He did not know what an ‘hour’ was nor what a watch was, and had the vaguest ideas of money. We saw some 6 of the black tents of his tribe, clustered on the mountain side in the distance.

Kosakh is a Jacobite village of 32 houses. It had 46 families ten years ago, but 14 families have disappeared since then, the scarcity of 1892 having perhaps driven out most of the 14. In the massacre time Kurds of a neighbouring village carried off all its sheep and cattle , but Hassan

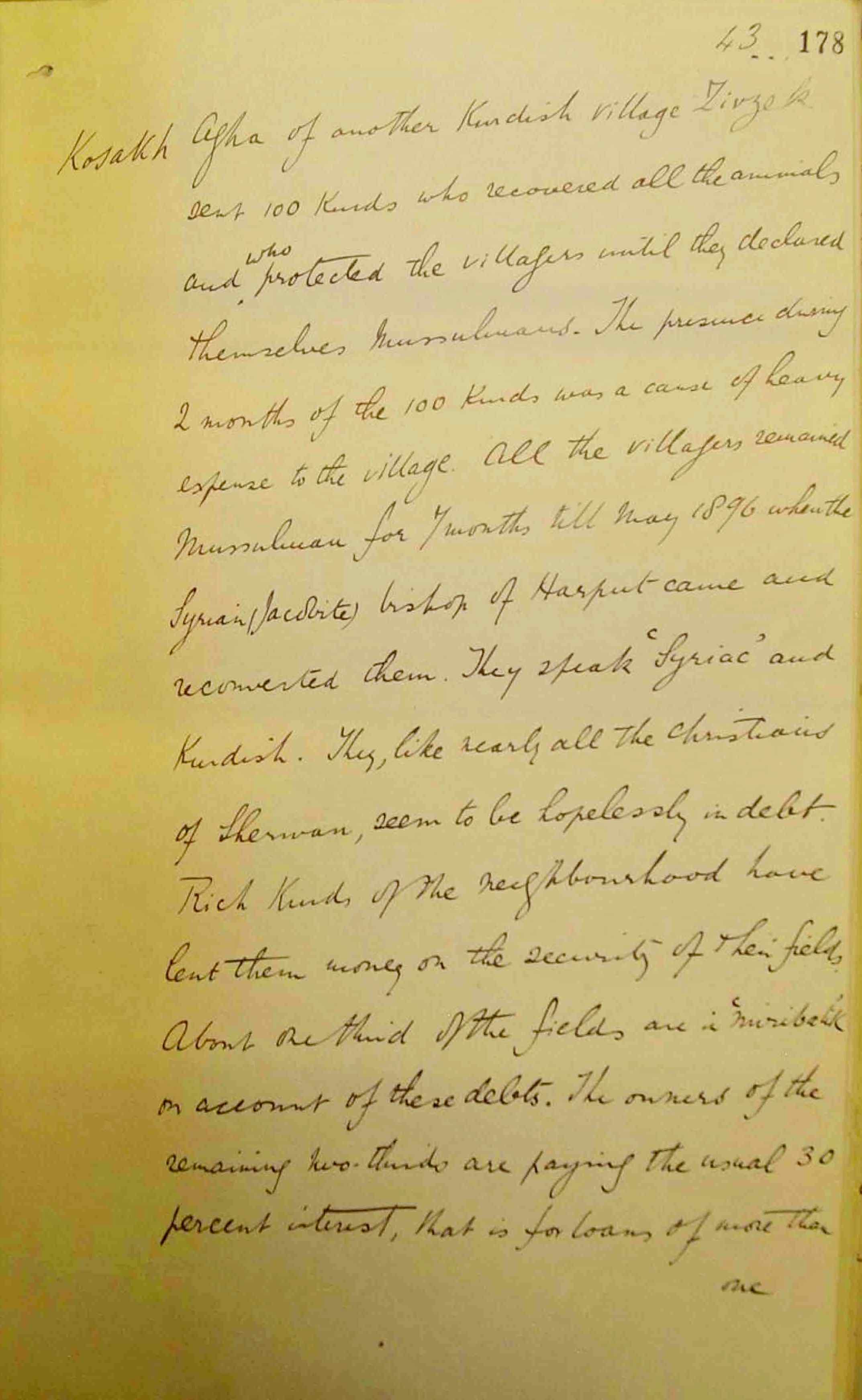

[178] Agha of another Kurdish village Zivzek sent 100 Kurds who recovered all the animals and who protected the villagers until they declared themselves Mussulmans. The presence during 2 months of the 100 Kurds was a cause of heavy expense to the village. All the villagers remained Mussulman for 7 months until May 1896 when the Syrian (Jacobite) bishop of Harput came and reconverted them. They speak ‘Syriac’ and Kurdish. They, like nearly all the Christians of Sherwan, seem to be hopelessly in debt. Rich Kurds of the neighbourhood have lent them money on the security of their fields. About one third of the fields are in ‘muribalik’ in account of the debts. The owners of the remaining two-thirds are paying the usual 30 percent interest, that is for loans of more than

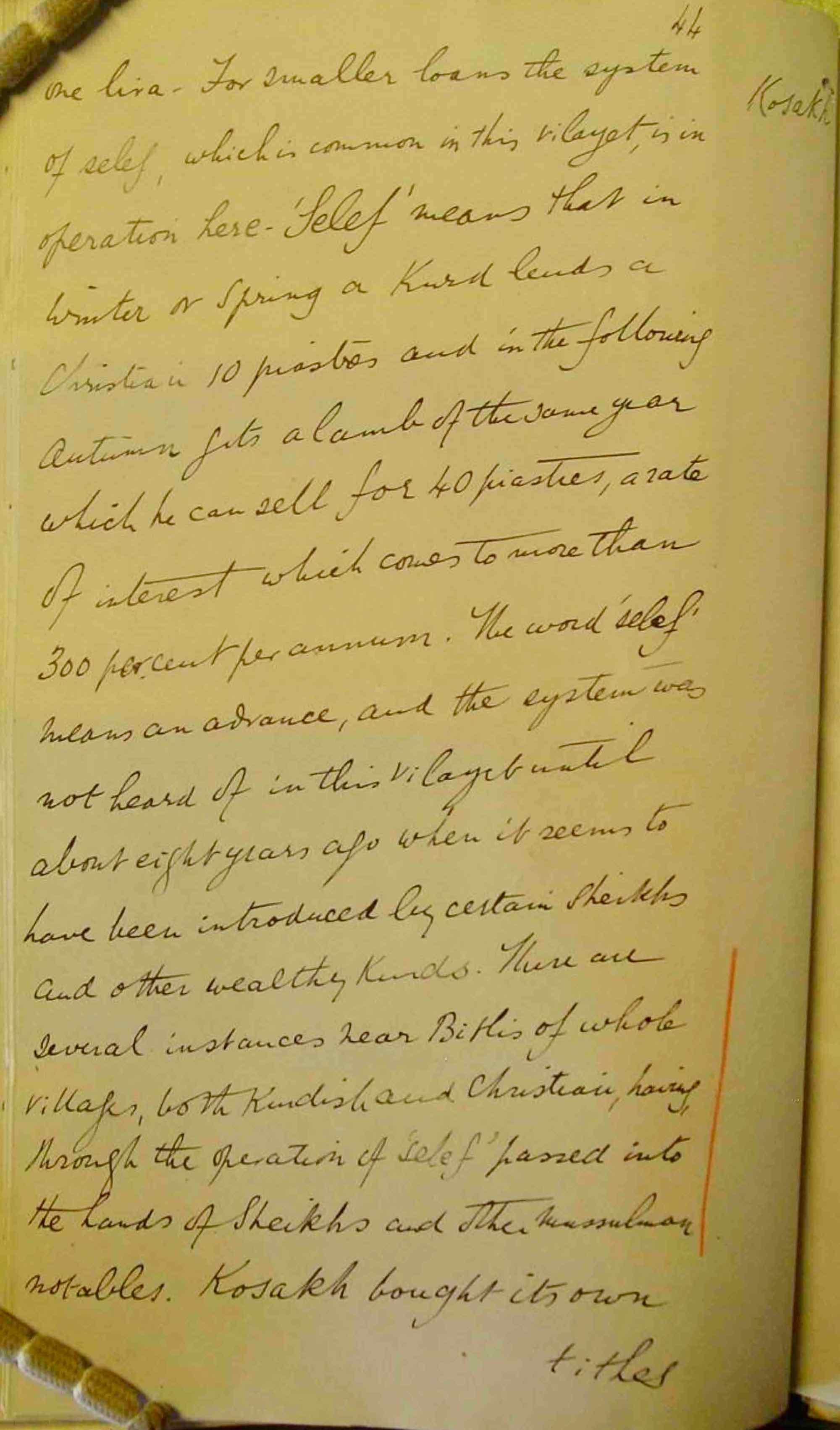

[178v] one lira. For smaller loans the system of selef, which is common in this vilayet, is in operation here. ‘Selef’ means that in winter or spring a Kurd lends a Christian 10 piasters and in the following autumn gets a lamb of the same year which he can sell for 40 piasters, a rate of interest which comes to more than 300 per cent per annum. The word ‘selef’ means and advance, and the system was not heard of in this vilayet until about eight years ago, when it seems to have been introduced by certain Sheikhs and other wealthy Kurds. There are several instances near Bitlis of whole villages, both Kurdish and Christian, having through the operation of ‘selef’ passed into the hands of Sheikhs and their Mussulman notables. Kosakh bought its own

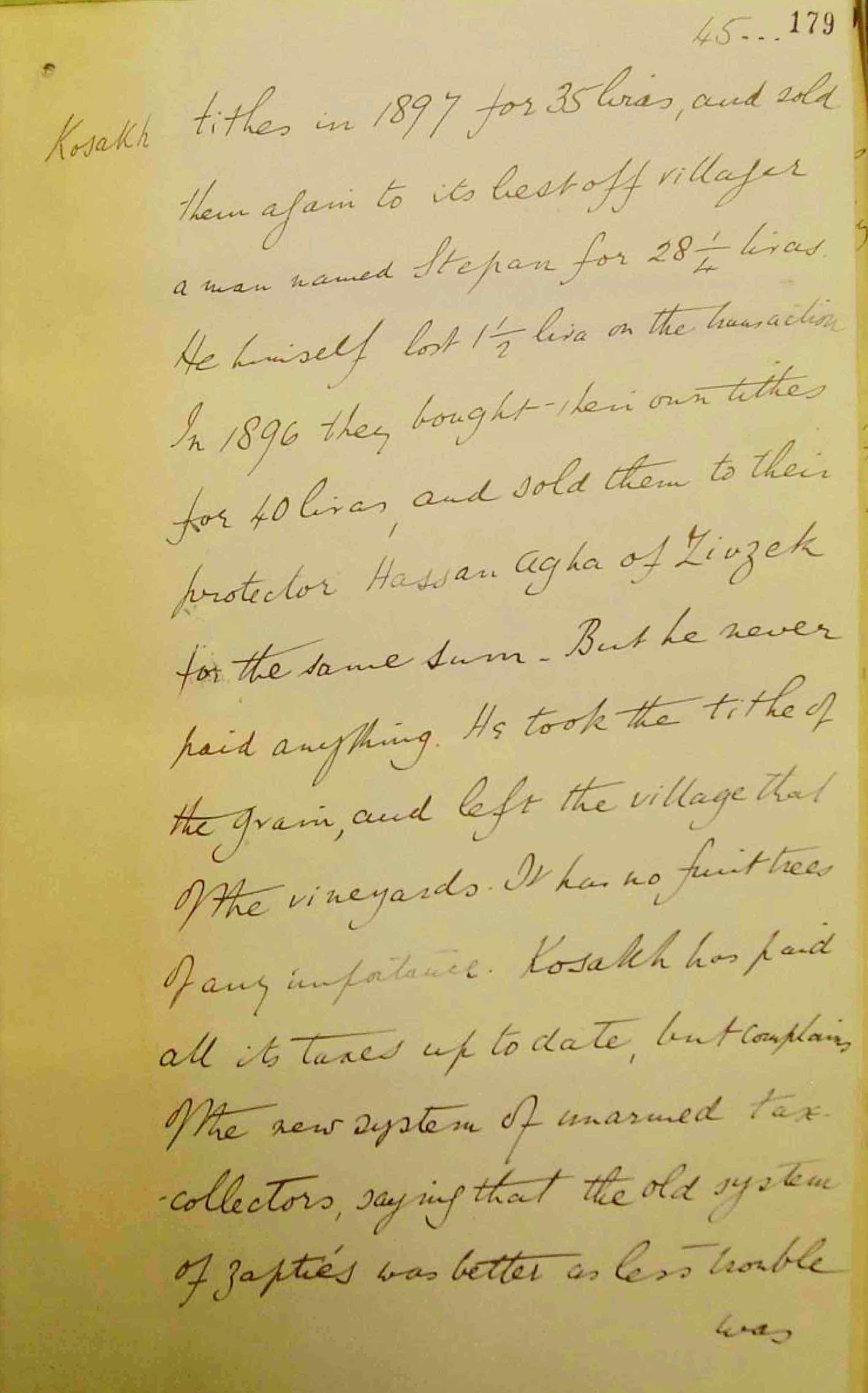

[179] tithes in 1897 for 35 liras, and sold them again to its least off villager a man named Stepan for 28 1/4 liras. He himself lost 1 1/2 lira on the transaction. In 1896 they bought their own tithes for 40 liras, and sold them to their protector Hassan Agha of Zivzek for the same sum. But he never paid anything. He took the tithe of the grain, and left the village that of the vineyards. It has no fruit trees of any importance. Kosakh has paid all its taxes up to date, but complains of the new system of unarmed tax collectors, saying that the old system of zaptiés was better as less trouble

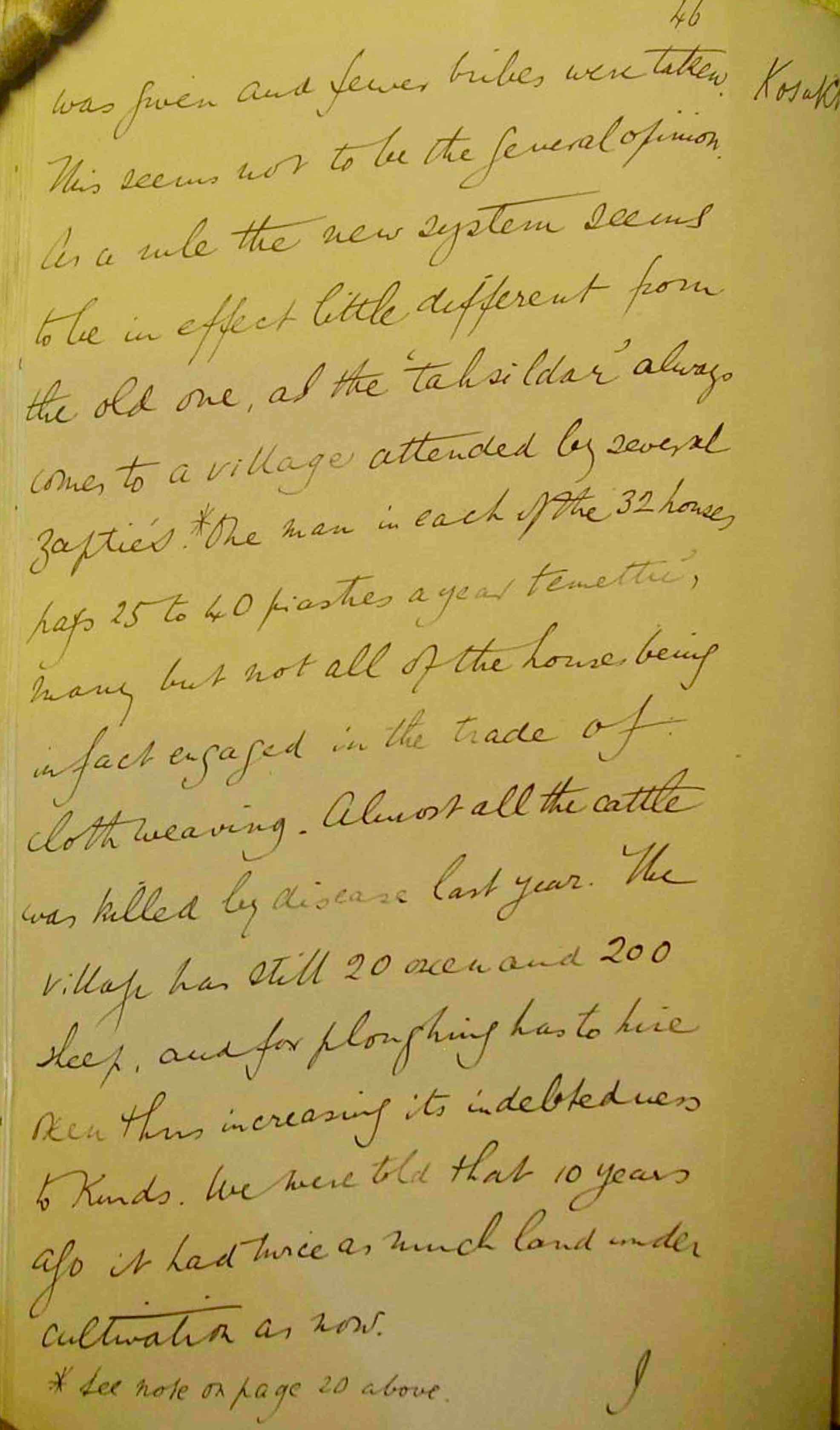

[179v] was given and fewer bribes were taken. This seems not to be the general opinion. As a rule the new system seems to be in effect little different from the old one, as the ‘tahsildar’ always comes to a village attended by several zaptiés. One man in each of the 32 houses pays 25 to 40 piasters a year temettu’, many but not all of the houses being in fact engaged in the trade of cloth weaving. Almost all the cattle was killed by disease last year. The village has still 20 oxen and 200 sheep, and for ploughing has to hire men thus increasing its indebtedness to Kurds. We were told that 10 years ago it had twice has much land under cultivation as now

[180]

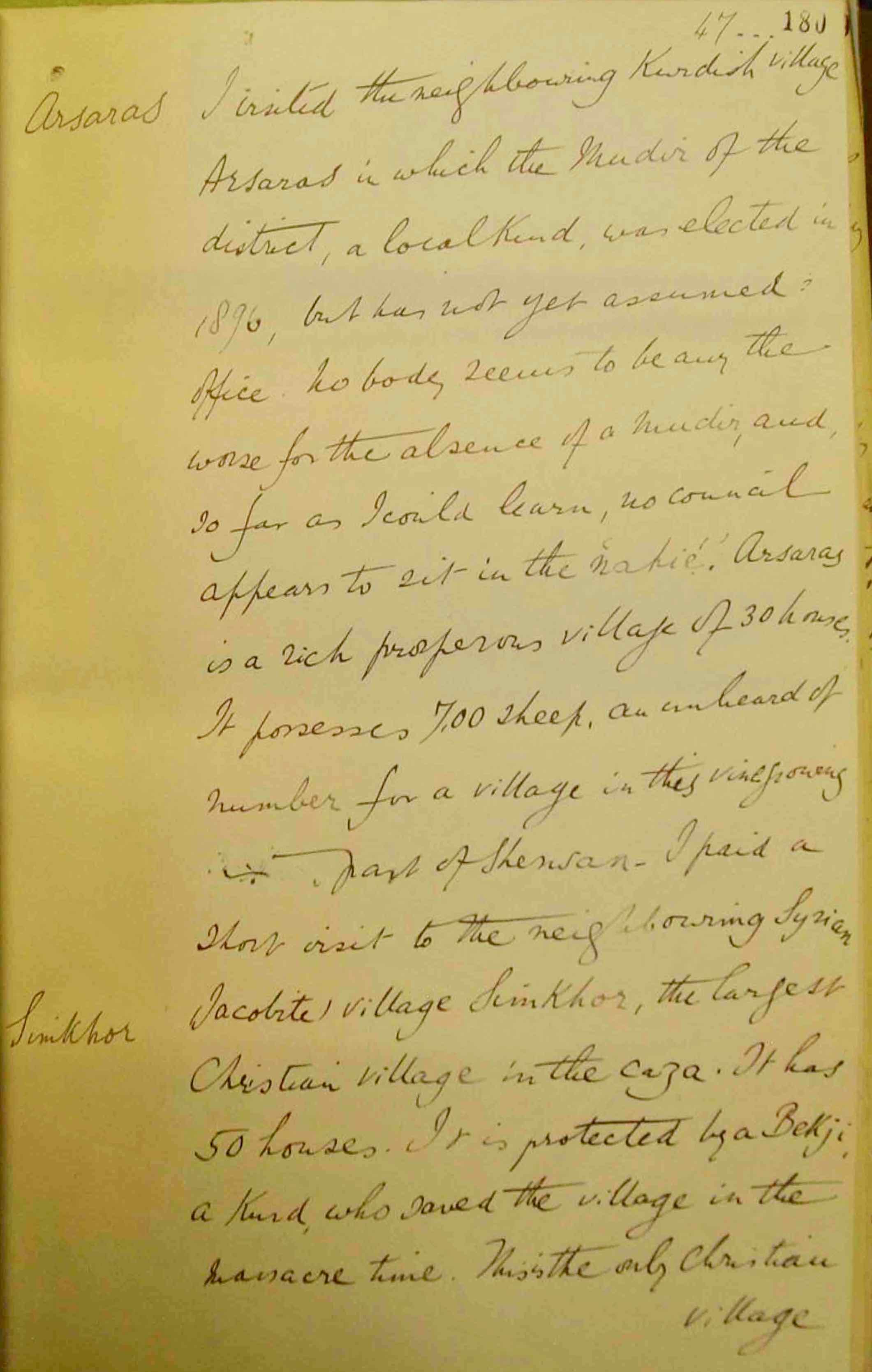

I visited the neighbouring Kurdish village of Arsaras in which the Mudir of the district, a local Kurd, was elected in 1896, but has not yet assumed office. Nobody seems to be … the worse for the absence of a mudir, and so far as I could learn, no council appears to sit in the nahié. Arsaras is a rich prosperous village of 30 houses. It possesses 700 sheep, an unheard of number for a village in this vine growing part of Shirwan. I paid a short visit to the neighbouring Syrian Jacobite village Simkhor, the largest Christian village in the caza. It has 50 houses. It is protected by a Bekdji, a Kurd, who saved the village in the massacre time. This the only Christian

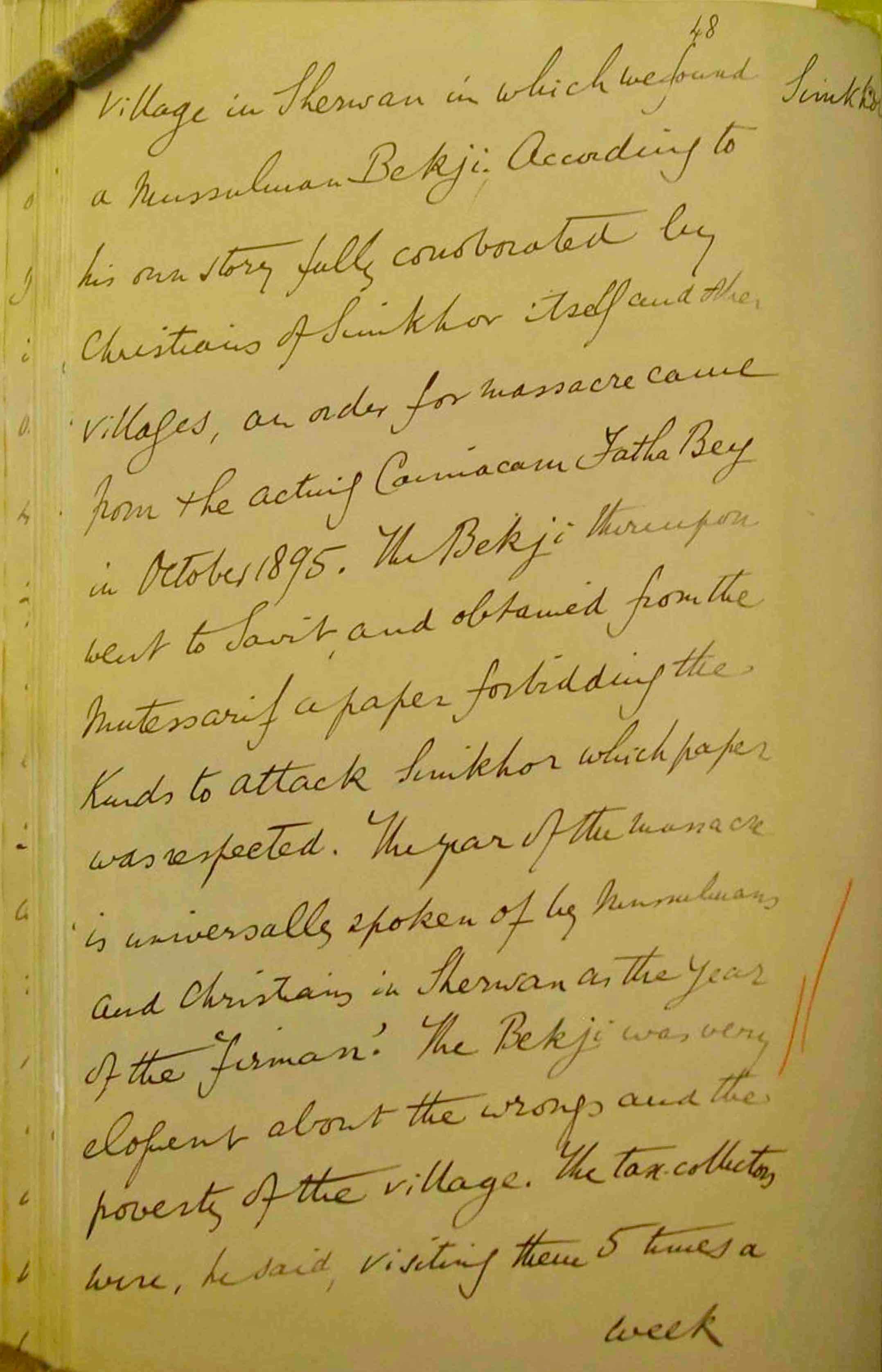

[180v] village in Sherwan in which we found a Mussulman Bekji. According to his own story fully corroborated by Christians of Simkhor itself and other villages, an order for massacre came from the acting Caimacam Fatha Bey in October 1895. The Bekdji thereupon went to Sairt, and obtained from the Mutessarif a paper forbidding the Kurds to attack Simkhor which paper was respected. The year of the massacre is universally spoken of by Mussulmans and Christians in Sherwan as the year of the Firman’. The Bekji was very eloquent about the wrongs and the poverty of the village. The tax collectors were, he said, visiting them 5 times a

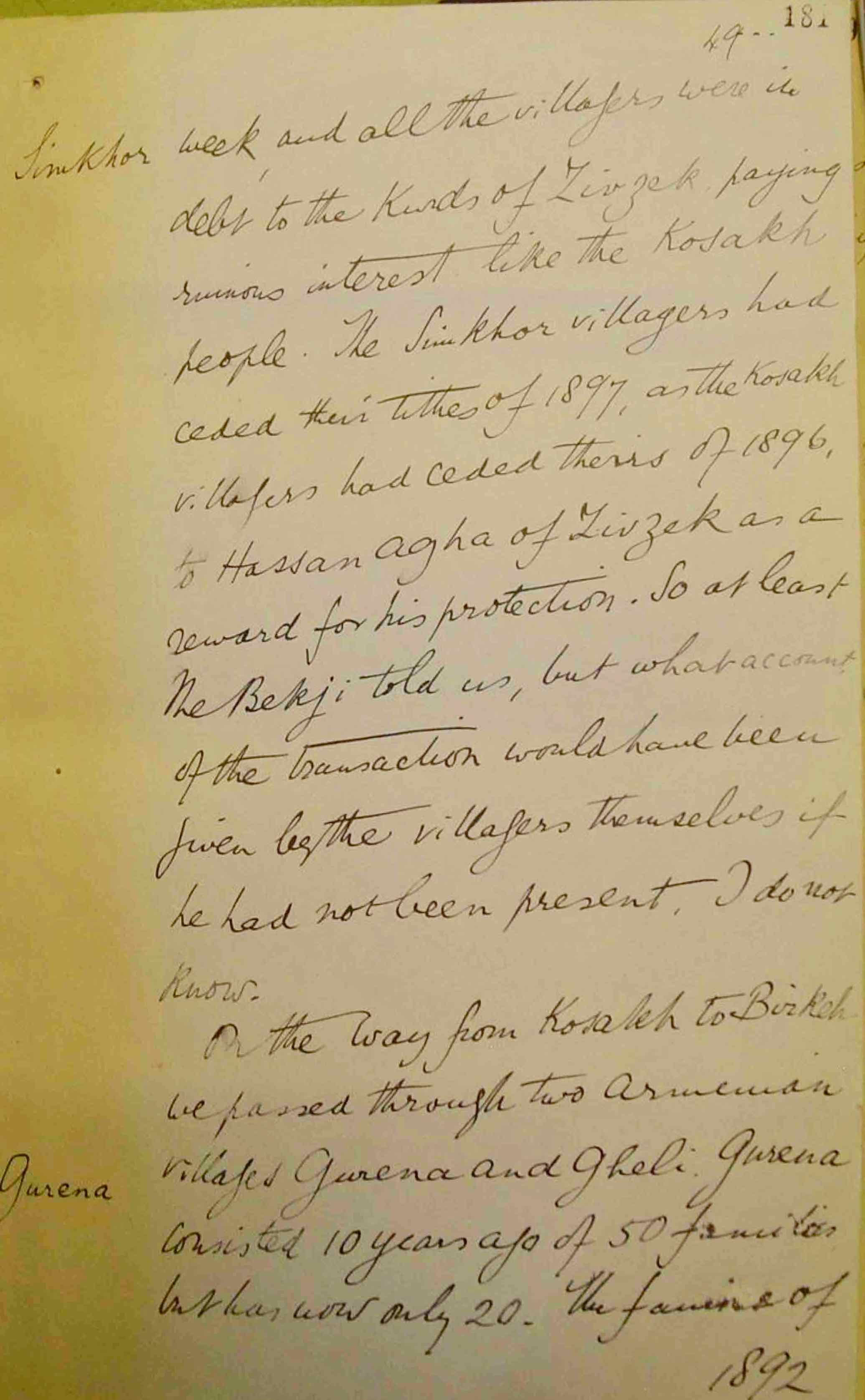

[181] week and the villagers were in debt to the Kurds of Zivzek, paying ruinous interest like the Kosakh people. The Simkhor villagers had ceded their tithes of 1897, as the Kosakh villagers had ceded theirs of 1896to Hassan Agha of Zivzek as a reward for his protection. So at least the Bekji told us, but what account of the transaction would have been given by the villagers themselves if he had not been present. I do not know.

On the way from Kosakh to Birkeh we passed through two Armenian villlages Gurena and Gheli. Gurena consisted 10 years ago of 50 families but has now only 20. The famine of

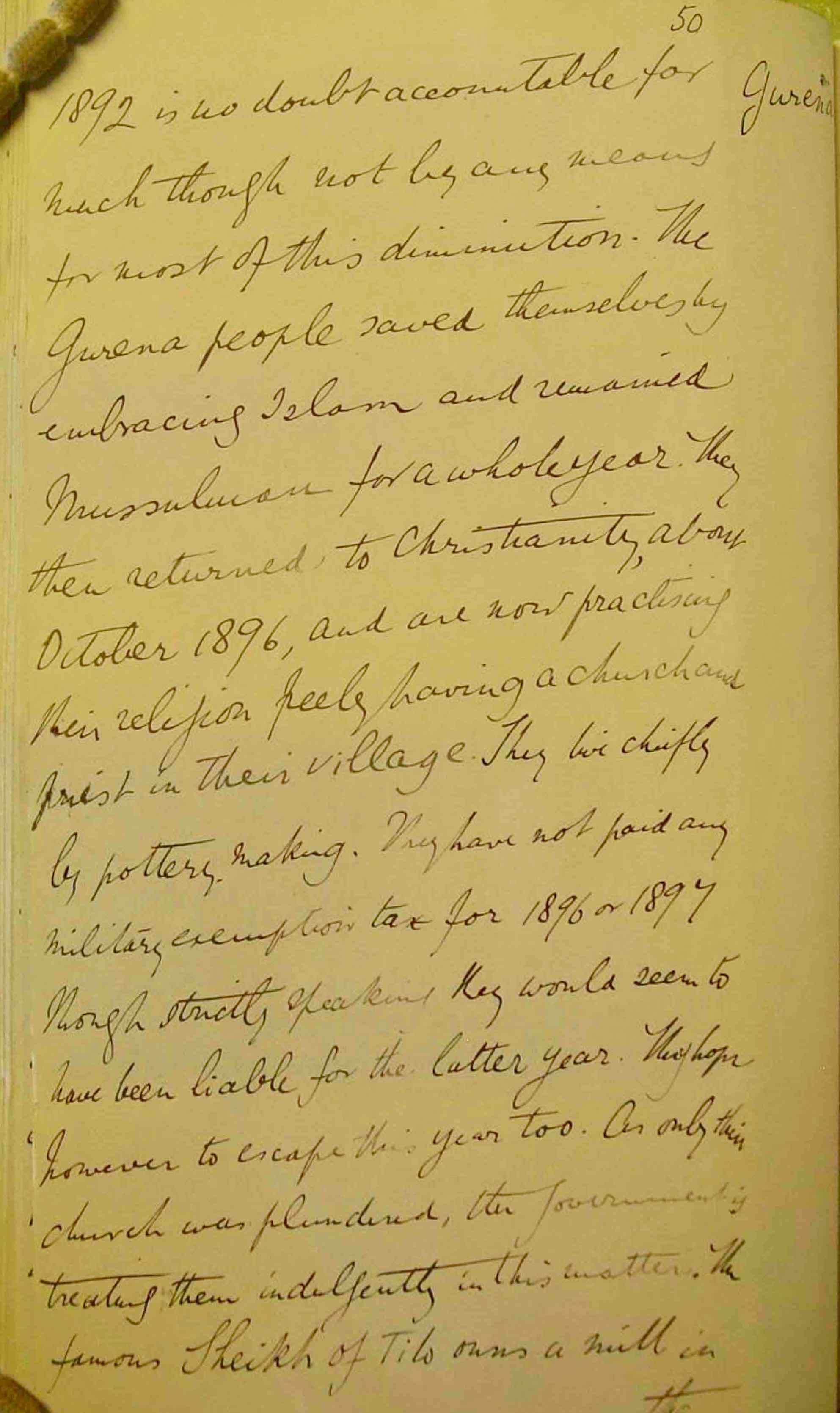

[181v] 1892 is no doubt accountable for much though not by any means for most of this diminution. The Gurena people saved themselves by embracing Islam and remained Mussulman for a whole year. They then returned to Christianity, about 1896, and are now practising their religion freely, having a church and priest in their village. They live chiefly by pottery making. They have not paid any military exemption tax for 1896 and 1897 though strictly speaking they would seem to have been liable for the latter year. They hope however to escape this year too. As only their church was plundered, the government is treating indifferently in this matter. The famous Sheikh of Tilo owns a mill in

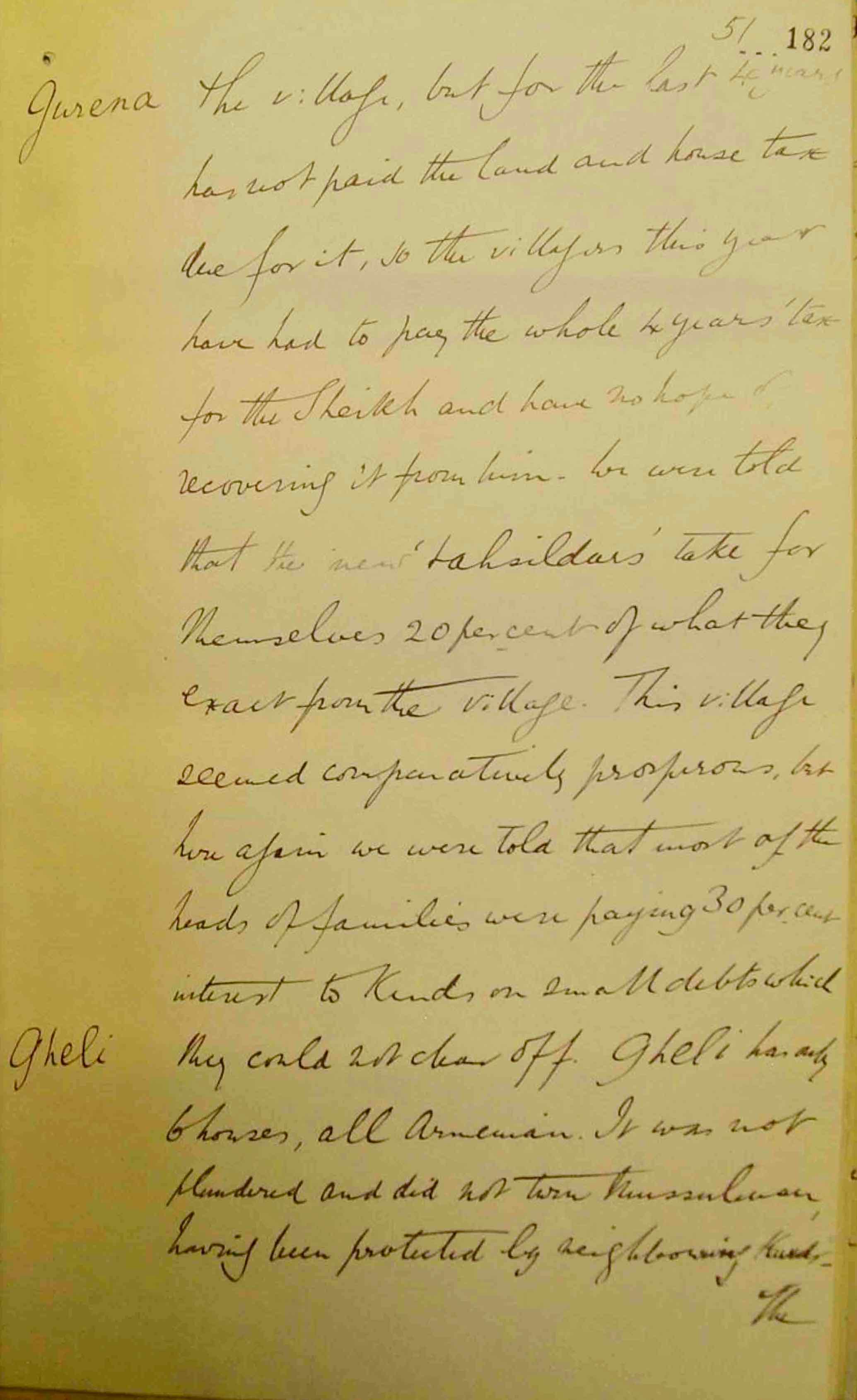

[182] the village, but for the last 4 years has not paid the land and house tax due for it, so the villagers this year have had to pay the whole 4 years tax for the Sheikh and have no hope of recovering it from him. We were told that the new tahsildars take from themselves 20 percent of the what they exact from the village. This village seemed comparatively prosperous , but here again we were told that most of the heads of families were paying 30 percent interest to Kurds on small debts which they could not clear off. Gheli has only 6 houses, all Armenian. It was not plundered and did not turn Mussulman having been protected by neighbouring Kurds.

Gheli → Durankaya village (Şirvan district, Siirt province)

pages 174v - 182