19th century sources

website of Jelle Verheij, historian

home | publications | pictures | historical pictures | travel snap shots | monuments | 19th century sources | research tools | links | contact

Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh May and June 1898

(by J.H. Monahan, British Vice-Consul in Bitlis)

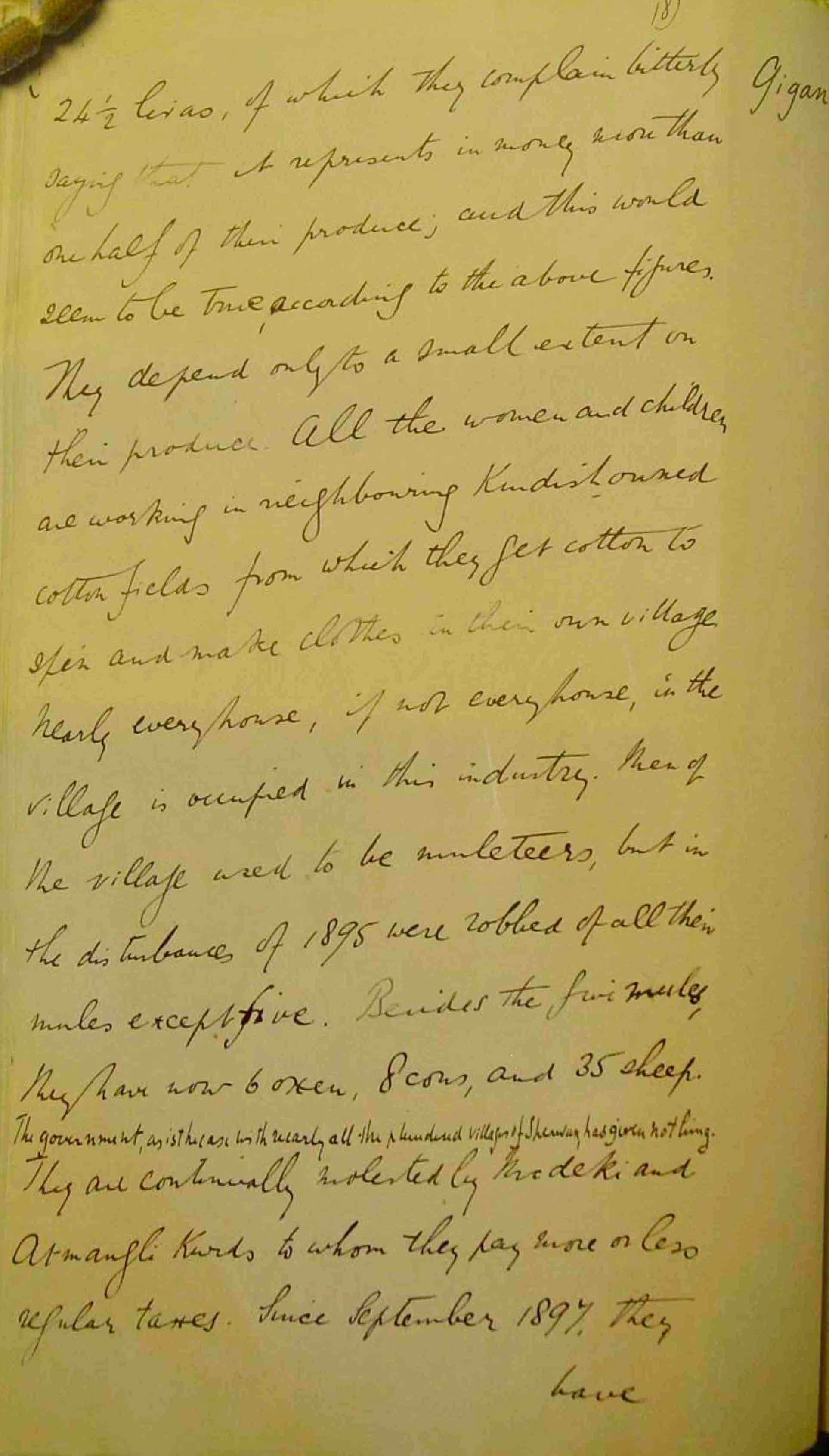

[165v] 24 1/2 liras, of which they complain bitterly saying that it represents in money more than one half of their produce; and this would seem to be true, according to the above figures. They depend only to a small extent on their produce. Al the women and children are working in neighbouring Kurdish owned cotton fields from which they get cotton to spin and make clothes in their own village. Nearly every house, of not every house, in the village is occupied in this industry. Men of the village used to be muleteers, but in the disturbances of 1895 were robbed of all their mules except five. Besides the five mules, they have now 6 oxen, 8 cows, and 35 sheep. The Government, as it the case with nearly all the plundered villages of Sherwan, has given nothing. The are continually molested by Modeki and Atmangli Kurds, to whom they pay more or less regular taxes. Since September 1897, they

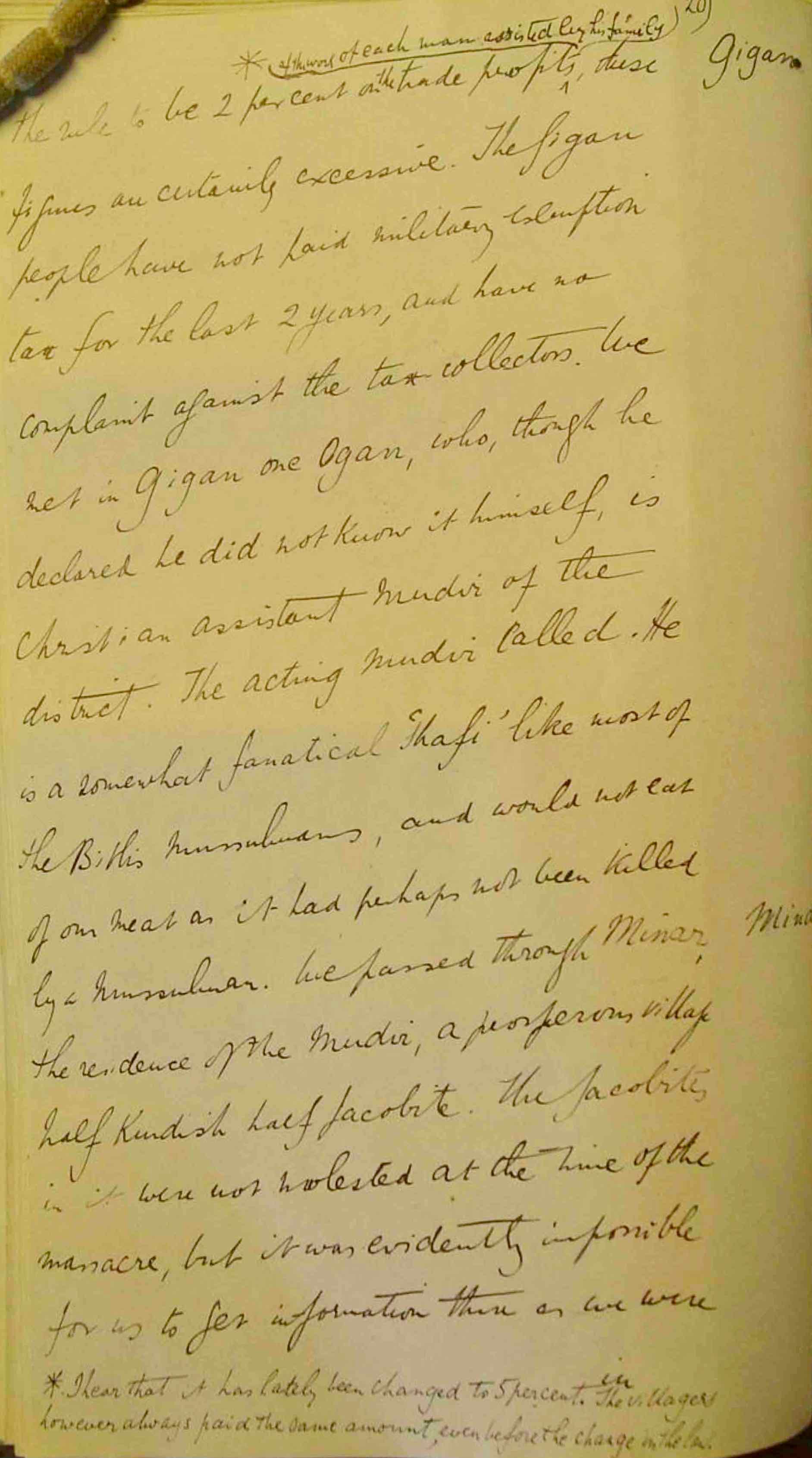

[166v] the rule to be 2 percent on the trade profits, of the worst? of each man assisted by his family1, these figures are certainly excessive. The Gigan people have not paid military exemption tax for the last 2 years, and have no complaints against the tax collectors. We met in Gigan one Ogan, who, though he declared he did not know it himself, is Christian assistant Mudir of the district. The acting Mudir called. He is a somewhat fanatical Shafi, like of most of the Bitlis Mussulmans, and would not eat of our meat as it had perhaps not been killed by a Mussulman. We passed through Minar, the residence of the Mudir, prosperous village half Kurdish half Jacobite. The Jacobites in it were not molested at the time of the massacre, but it was evidently impossible for us to get information there as we were

1) I hear it has lately been changed to 5 percent. The villagers however always paid the same amount, even before the change in the law.

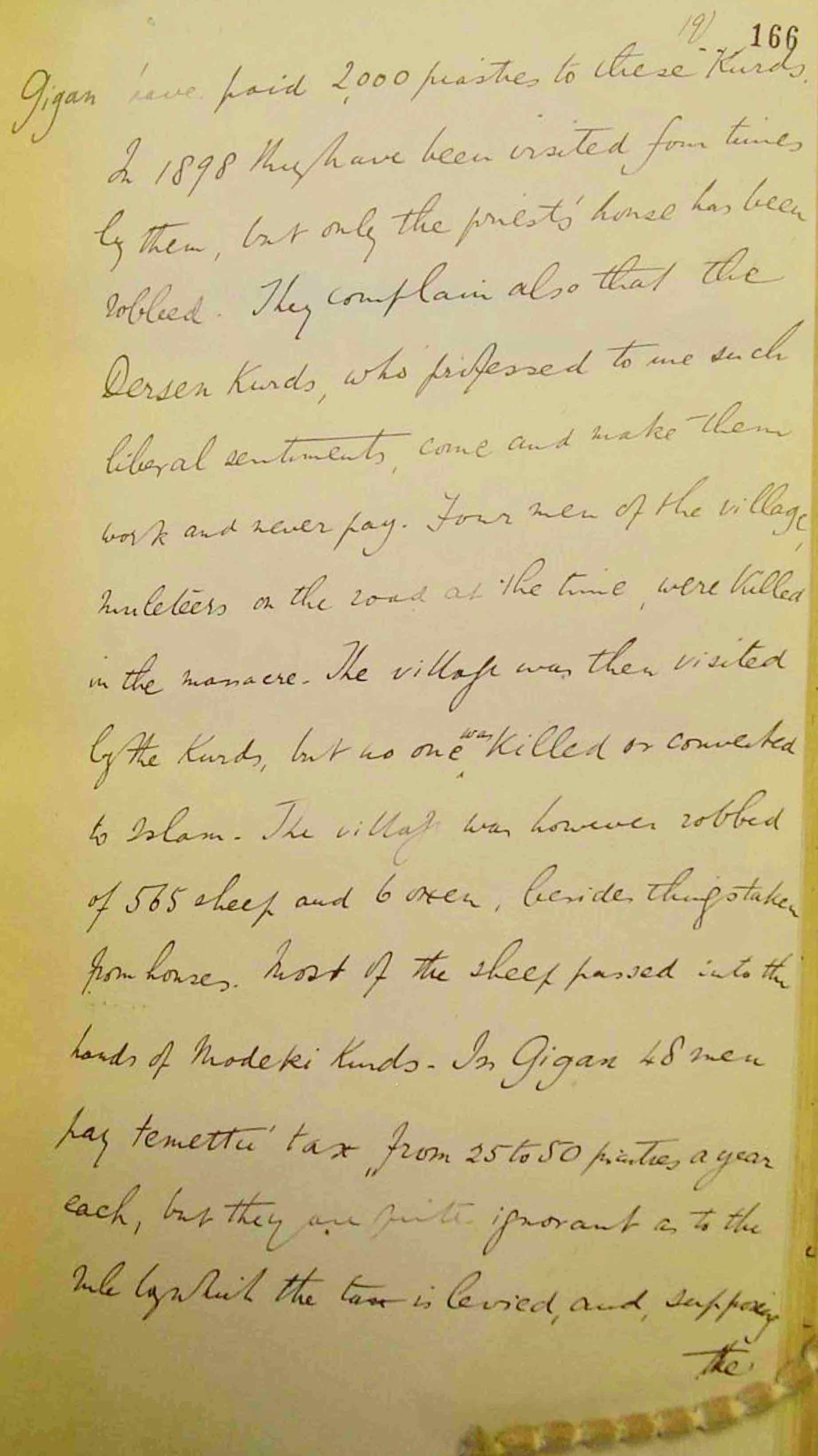

[166] have paid 2,000 piasters to these Kurds. In 1898 they have been visited four times by them, but only the priest’s house has been robbed. They complained also that the Dersen Kurds, who professed to me such liberal sentiments, come and make them work and never pay. Four men of the village, muleteers on the road at the time. were killed in the massacre. The village was then visited by the Kurds, but no one was killed or converted to Islam. The village was however robbed of 565 sheep and 6 oxen, besides things taken from houses. Most of the sheep passed into the hands of Modeki Kurds. In Gigan 48 men pay temettu tax from 25 to 50 piasters a year each, but they are quite ignorant as to the rule by which the tax is levied, and supposing

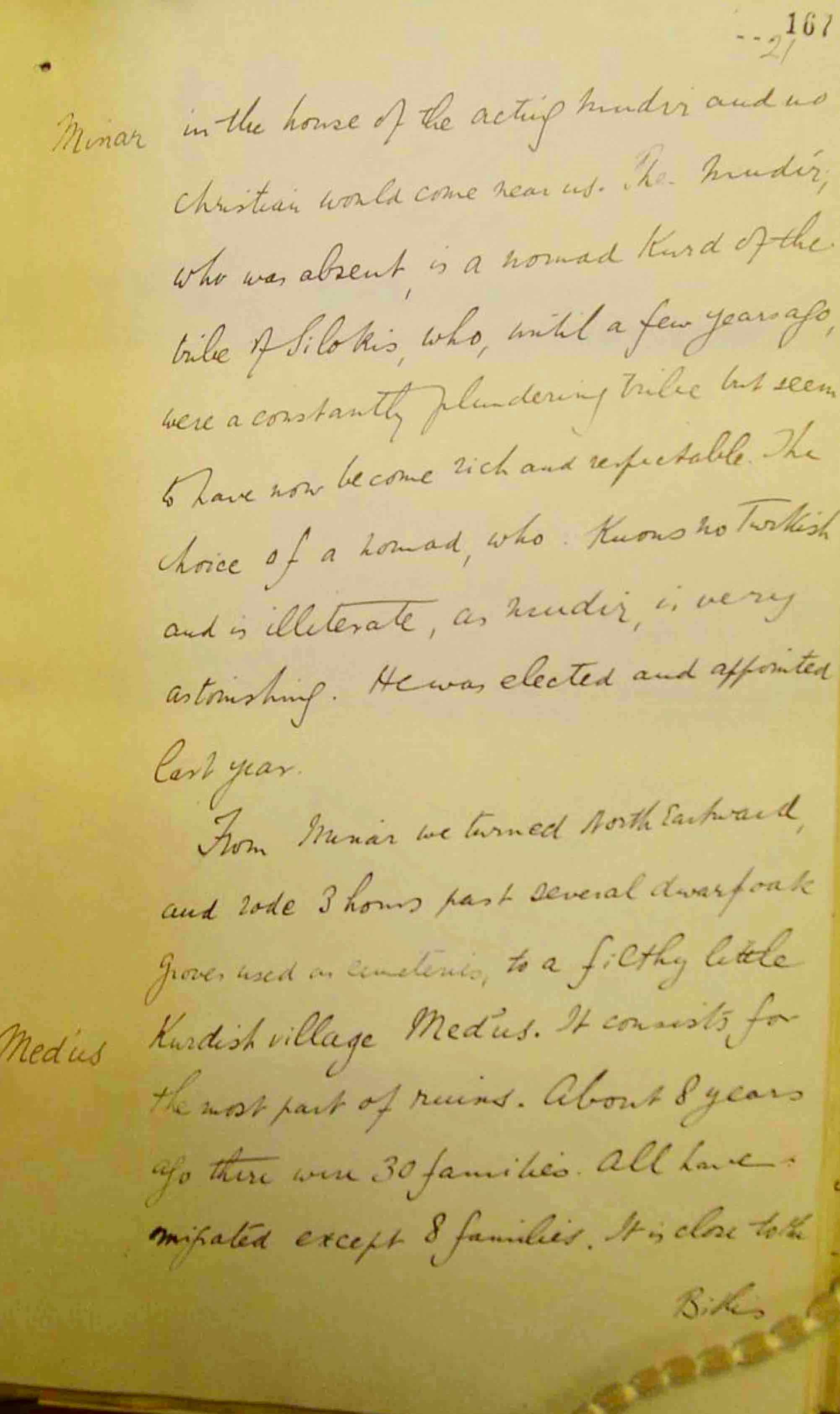

[167] in the house of the acting Mudir and no Christian would come near to us. The Mudir, who was absent, is a nomad Kurd of the tribe of Silokis, who, until a few years ago, were a constantly plundering tribe but seem to have now become rich and respectable. The choice of a nomad, who knows no Turkish and is illiterate, as Mudir, is a very astonishing. He was elected and appointed last year.

From Minar we turned North Eastward and rode 3 hours past several dwarf groves used in cemeteries, to a filthy little Kurdish village Med’us. It consists for the most part of ruins. About 8 years ago there were 30 families. All have migrated except 8 families. It is close to the

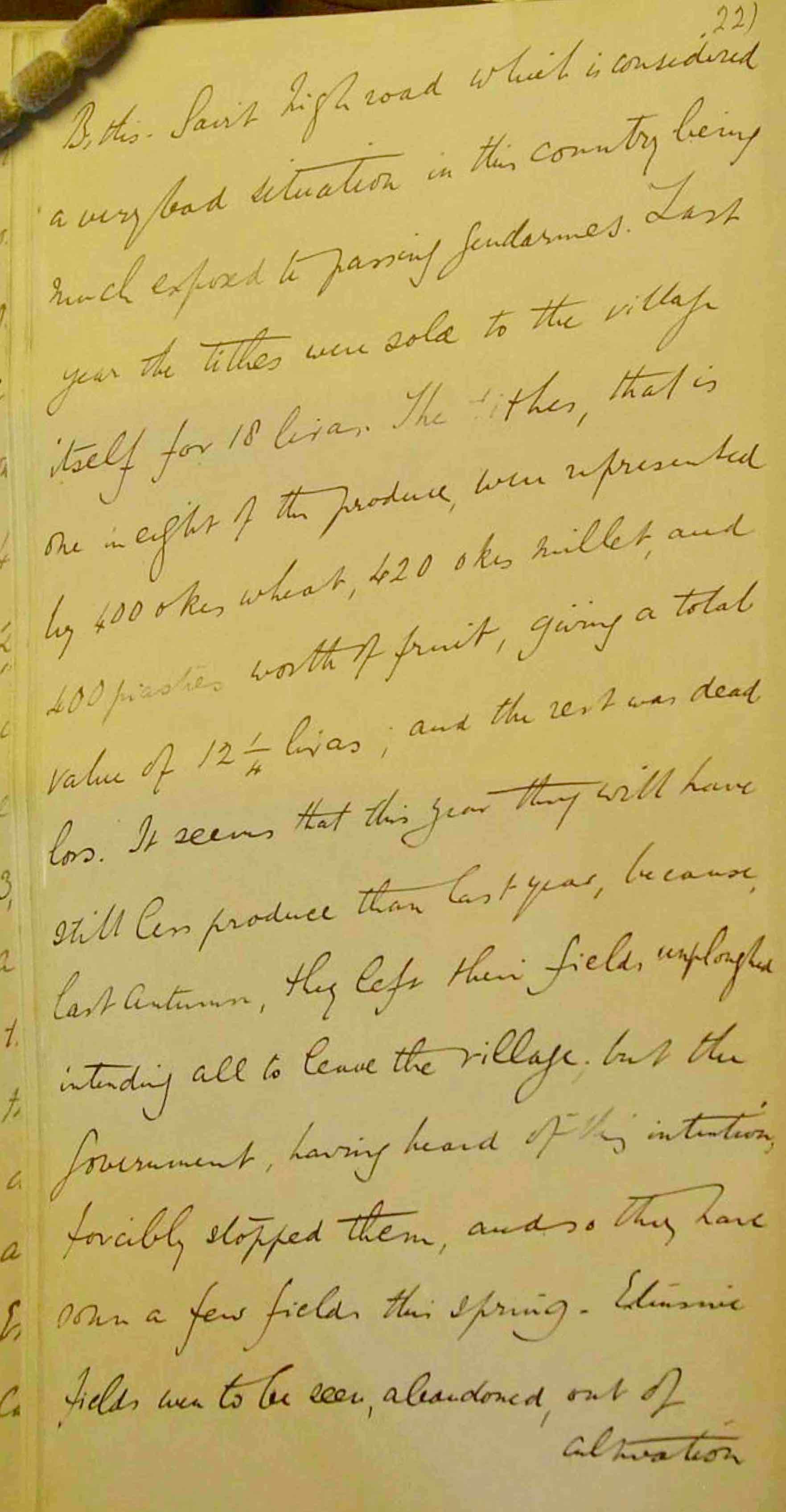

[167v] Bitlis-Sairt high road which is considered a very bad situation in a country being much exposed to passing gendarmes. Last year the tithes were sold to the village itself for 18 liras. The tithes, that is one eight of the produce, were represented by 400 okes wheat, 420 okes millet, and 400 piasters worth of fruit, giving a total value of 12 1/4 liras, and the rest was dead loss. It seems that this year they will have still less produce than last year, because, last autumn, they left their fields unploughed intending all to leave the village, but the Government, having heard of their intention forcibly stopped them, and so they have sown a few fields in the spring. Elusive? fields were to be seen, abandoned, out of

[168] cultivation many of them had been so for years.

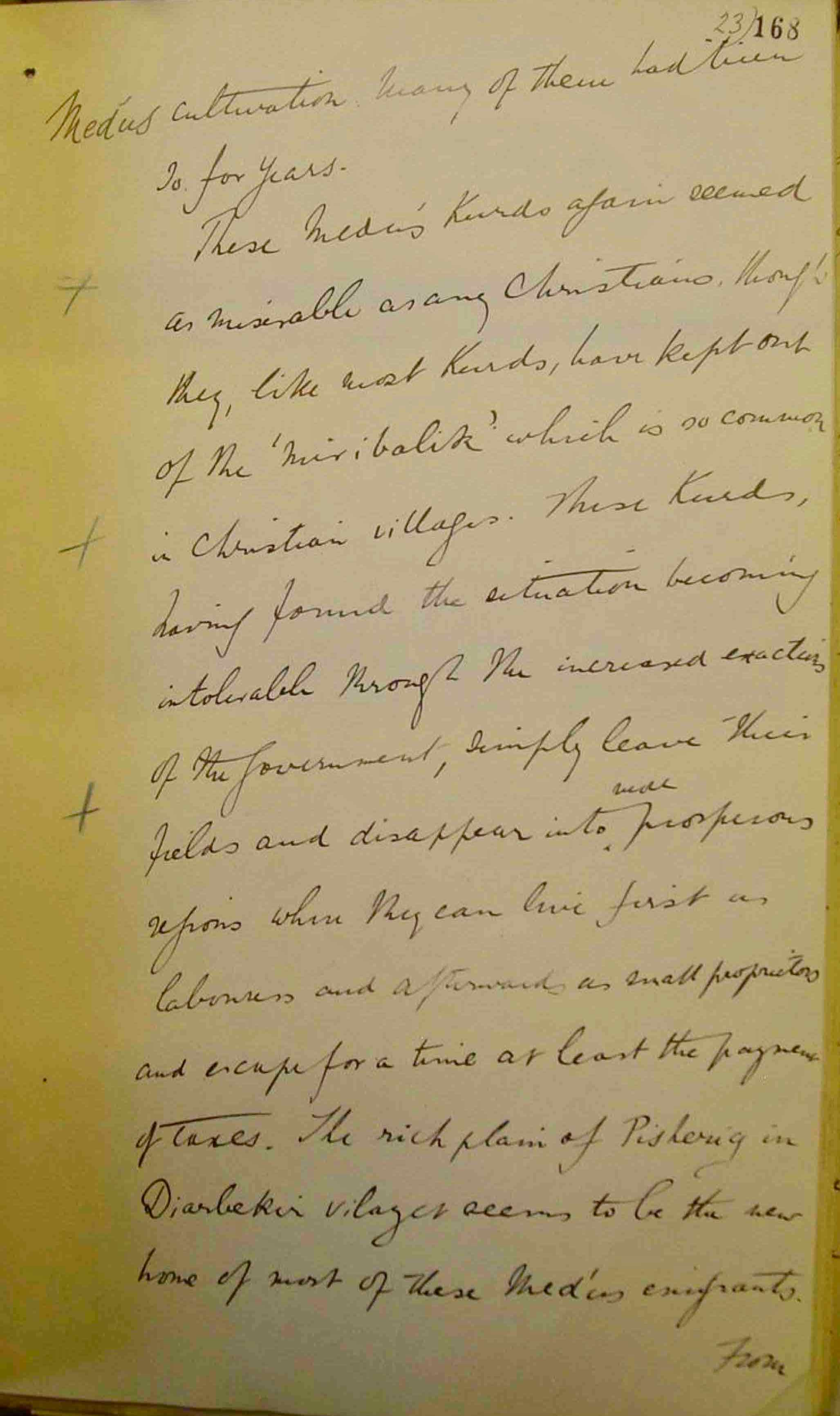

Those Med’us Kurds again? seemed as miserable as many Christians, though they, like most Kurds, have kept out of the “miribalik” which is so common in Christian villages. These Kurds, having found the situation becoming intolerable though the increasing exactions of the Government, simply leave their fields and disappear into more prosperous regions where they can live first as labourers and afterwards as small proprietors and escape for a time at least the payment of taxes. The rich plain of Pisherig in Diarbekir Vilayet seems to be the new home of most of these Med’us emigrants.

[168v]

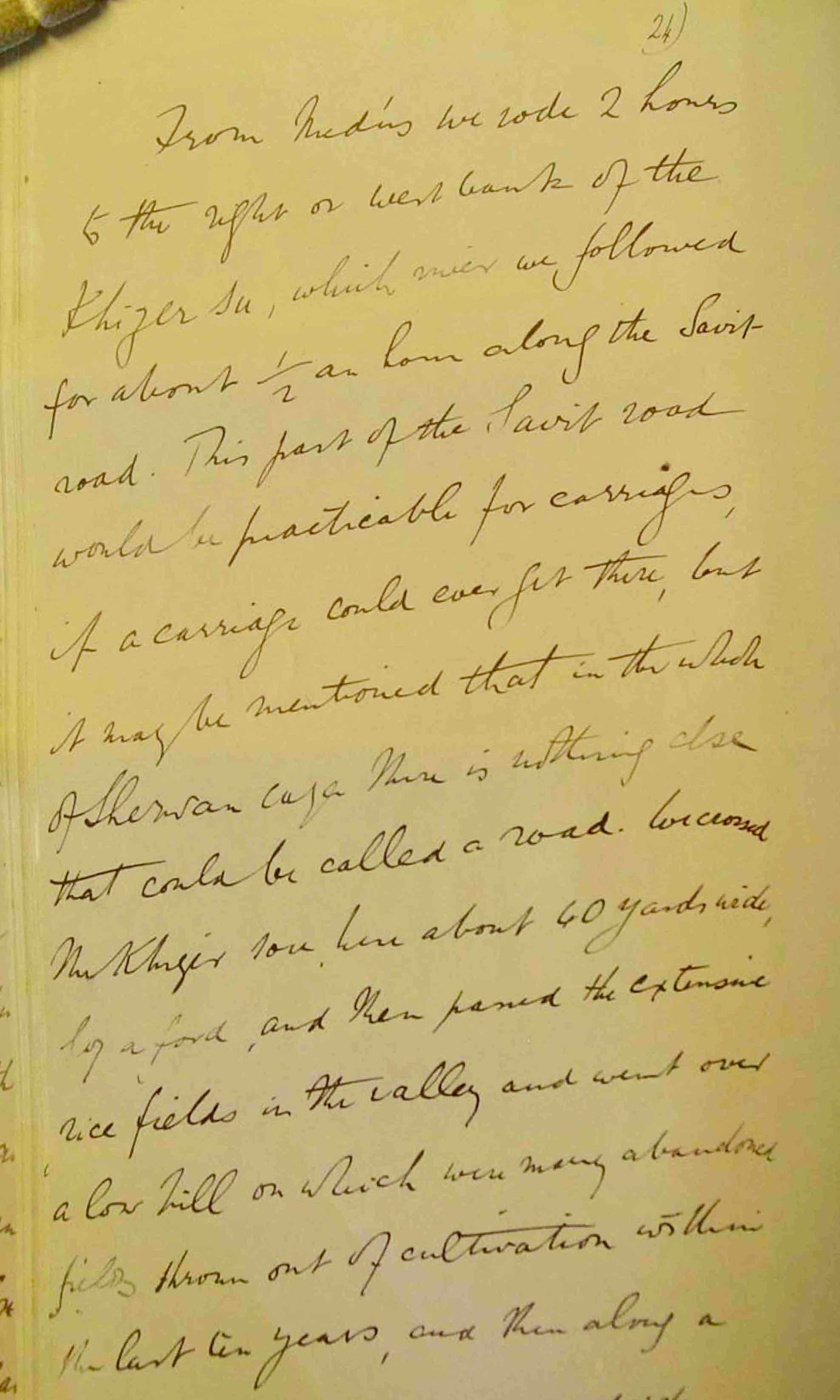

From Med’us we rode 2 hours to the right or west bank of the Khizer Su, which river we followed for about 1/2 an hour along the Sairt road. This part of the Sairt road would be practicable for carriages, if a carriage would ever fit there, but it may be mentioned that in the whole of Sherwan Caza there is nothing else that could be called a road. We crossed the Khizer Sou, here about 40 yards wide, by a ford, and then passed the extensive rice fields in the valley and went over a low hill on which were many abandoned fields thrown out of cultivation within the last ten years, and then along

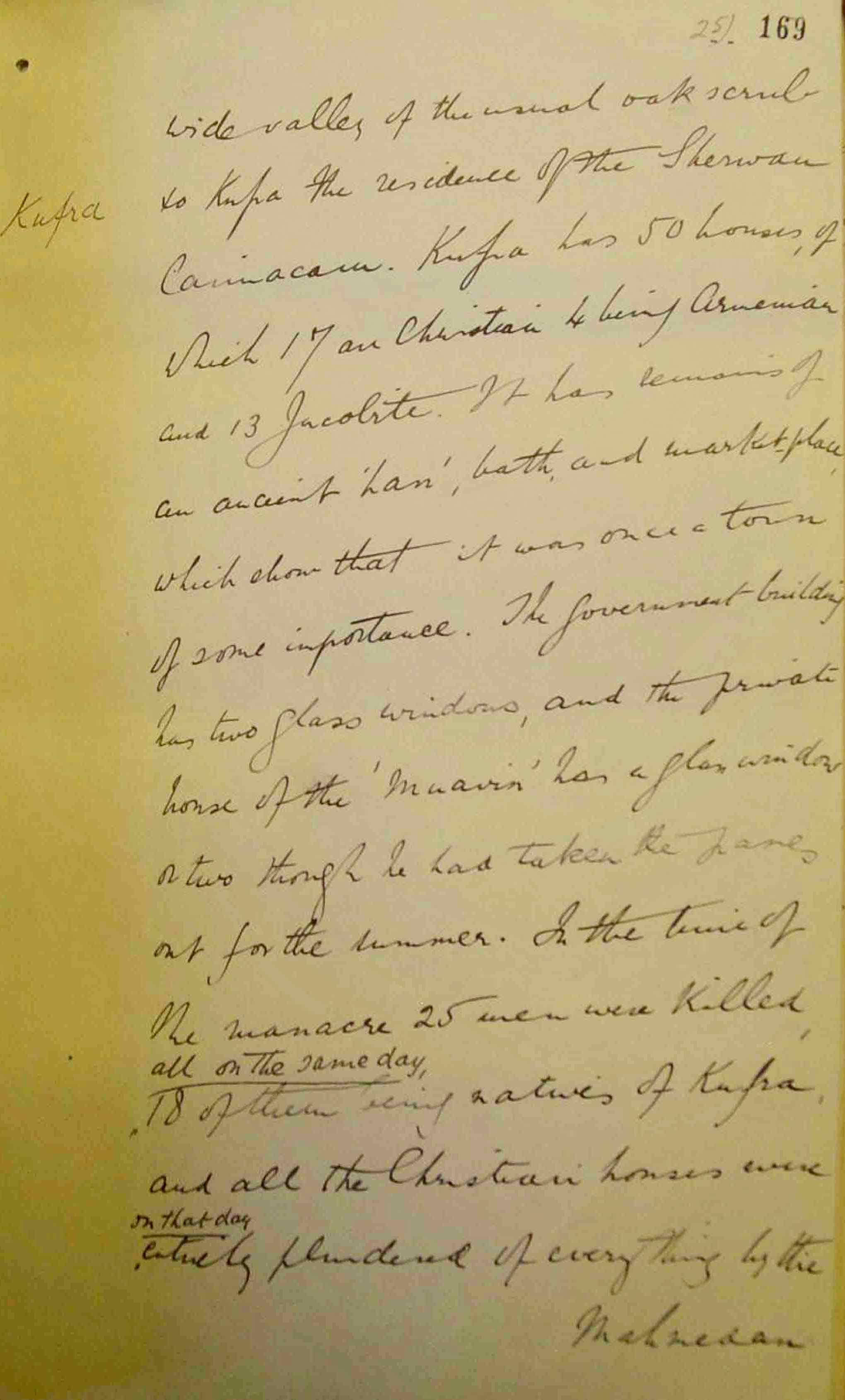

[169] wide valley of the usual oak scrub to Kufra, the residence of the Sherwan Caimacam. Kufra has 50 houses, of which 17 are Christian, 4 being Armenian, and 13 Jacobite. It has remains of an ancient “han”, bath, and marketplaces, which show that it was once a town of some importance. The Government building has two glass windows, and the private house of the “muavin” has a glass windows or two though he has taken the frames out for the summer. At the time? of the massacre 25 men were killed, all on the same day, 18 being natives of Kufra, and that all the Christian houses were on that day entirely plundered of everything by the

[169v] Mahomedan and Strugan nomads by permission of Fatha Bey, a local Sherwan notable, now dead, who was then acting caimacam. I will return to this further on in my report.

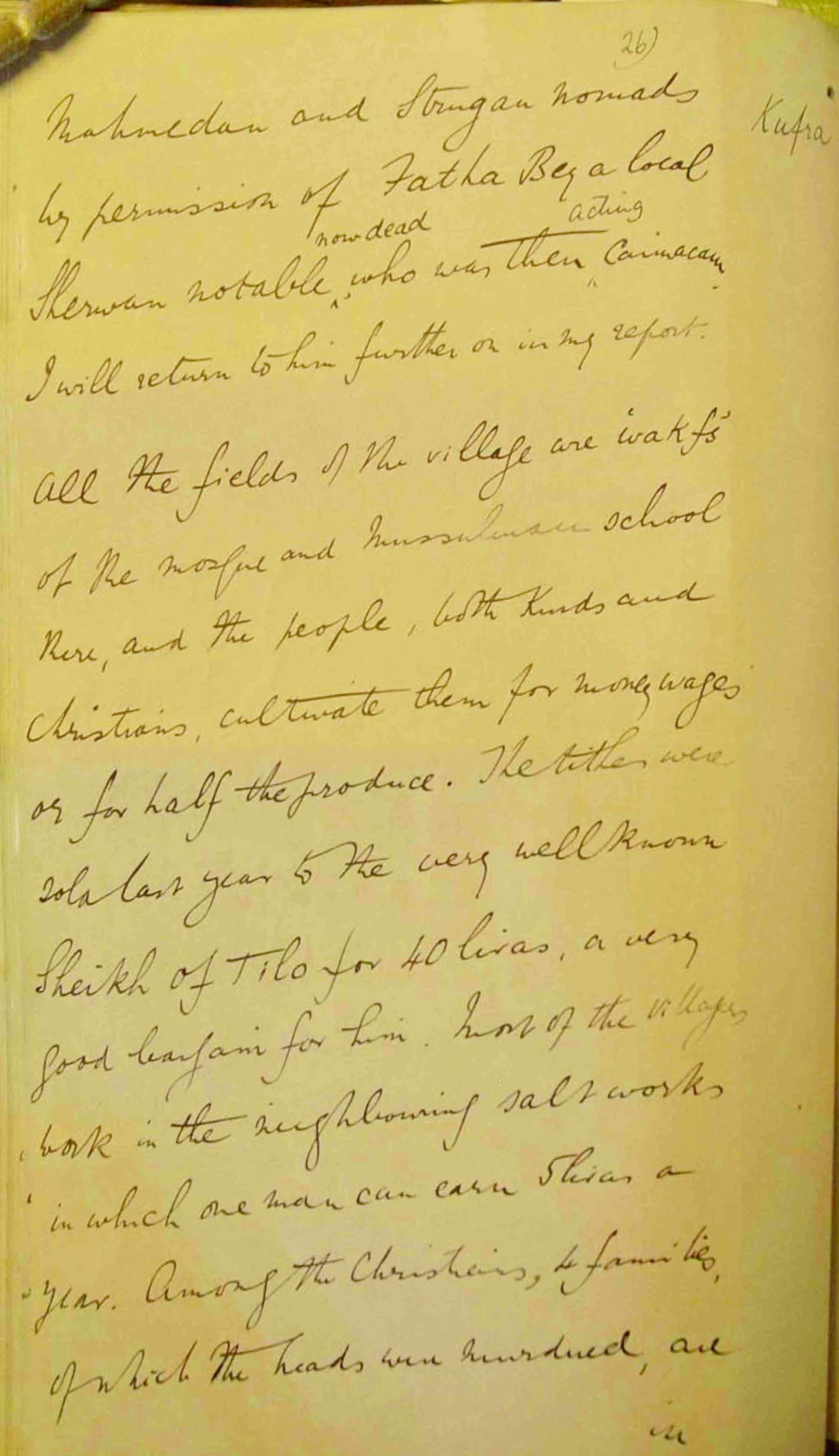

All the fields of the village are ‘wakfs’ of the mosquee and Mussulman school there, and the people, both Kurds and Christians, cultivate them for money or for half the produce. The tithes were sold last year to the very well known Sheikh of Tilo for 40 liras, a very good bargain for him. Most of the villagers work in the neighbouring salt works in which one man can earn 5 Liras a year. Among the Christians, 4 families, of which the heads were murdered, are

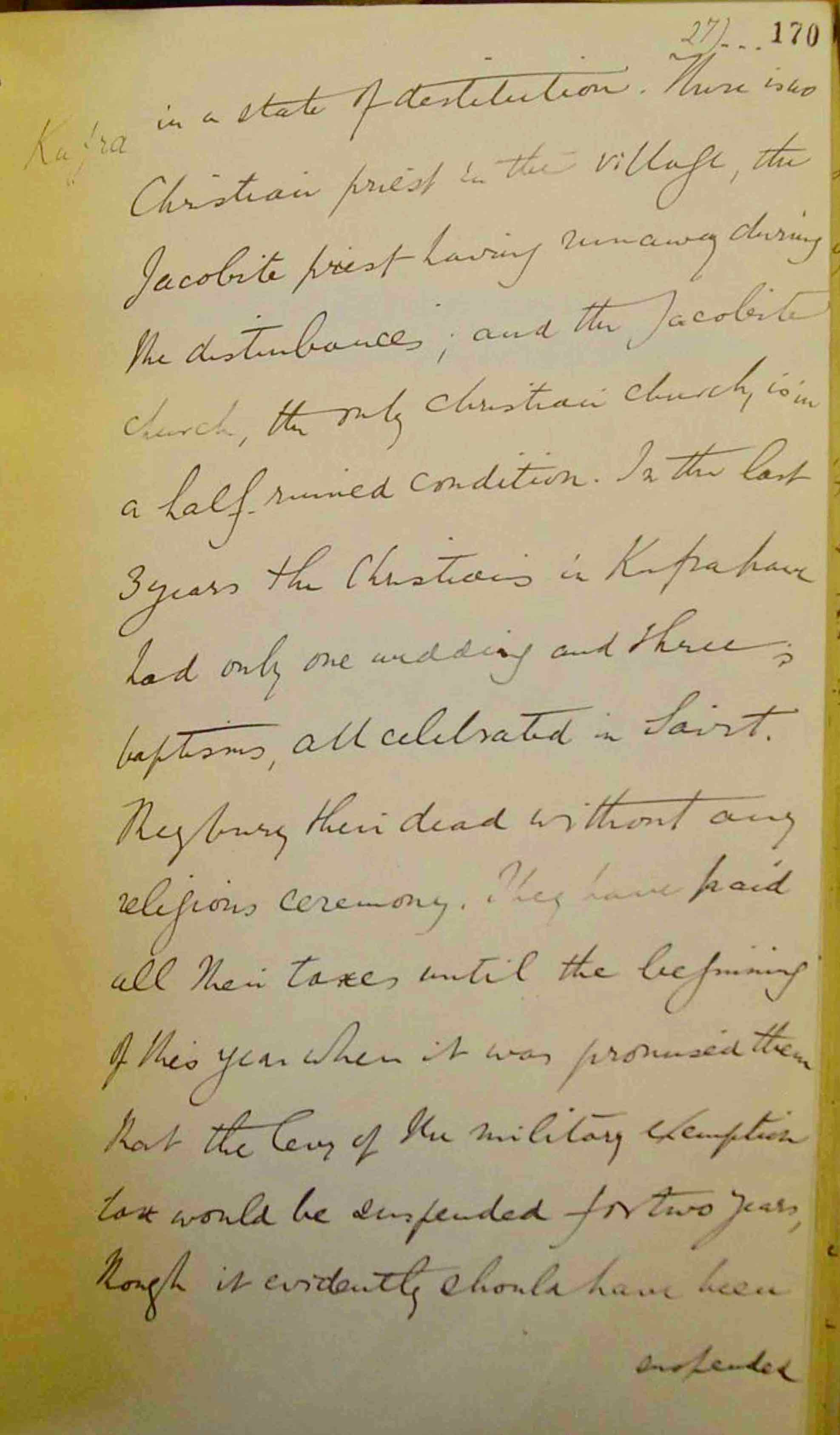

[170] in a state of destitution. There is no Christian priest in the village, the Jacobite priest having run away during the disturbances, and the Jacobite church, the only Christian church, is in a half-ruined condition. In the last 3 years the Christians in Kufra had only one wedding and three baptisms, all celebrated in Sairt. They bury their dead without any religious ceremony. They have paid all their taxes until the beginning of this year when it was promised them that the levy of the military exemption tax would be suspended for two years, though it evidently should have been

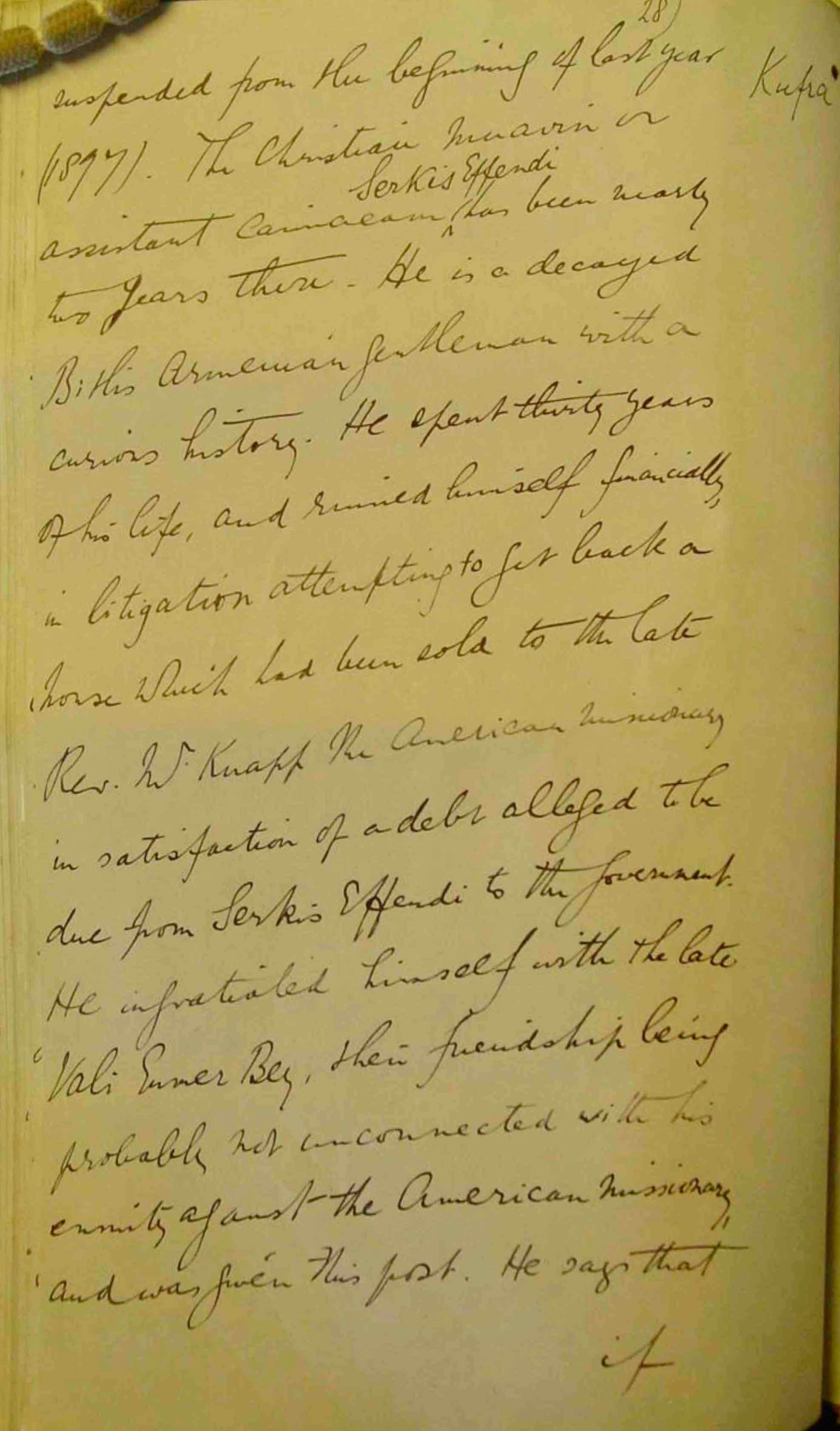

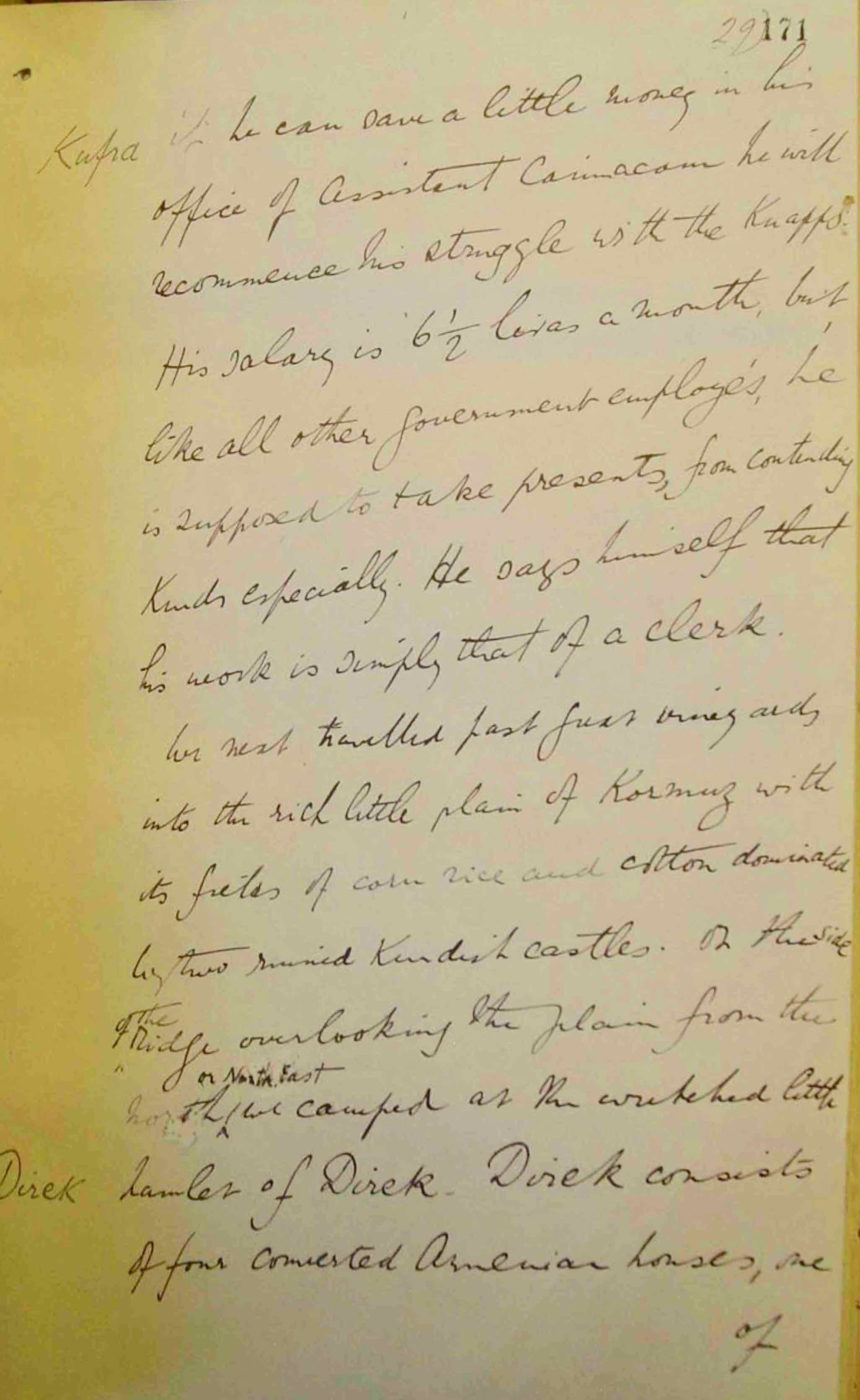

[170v] suspended from the beginning of last year (1897). The Christian mavin or assistant caimacam, Serkis Effendi, has been nearly two years there. He is a decayed Bitlis Armenian gentleman with a curious history. He spent thirty years of his life, and ruined himself financially, in litigation attempting to get back a house which has been sold to the late Rev. W. Knapp, the American missionary, in satisfaction of a debt alleged to be due from Serkis Effendi to the Government. He ingratiated himself with the late Vali Eumer Bey, their friendship being probably not unconnected with his enmity against the American missionary, and was given this post. He says that

[171] if we can save a little money in his office of Assistant Caimacam he will recommence his struggle with the Knapps. His salary is 6 1/2 liras a month, but like all other government employees, he is supposed to take presents, from contending Kurds especially. He says himself that his work is simply that of a clerk.

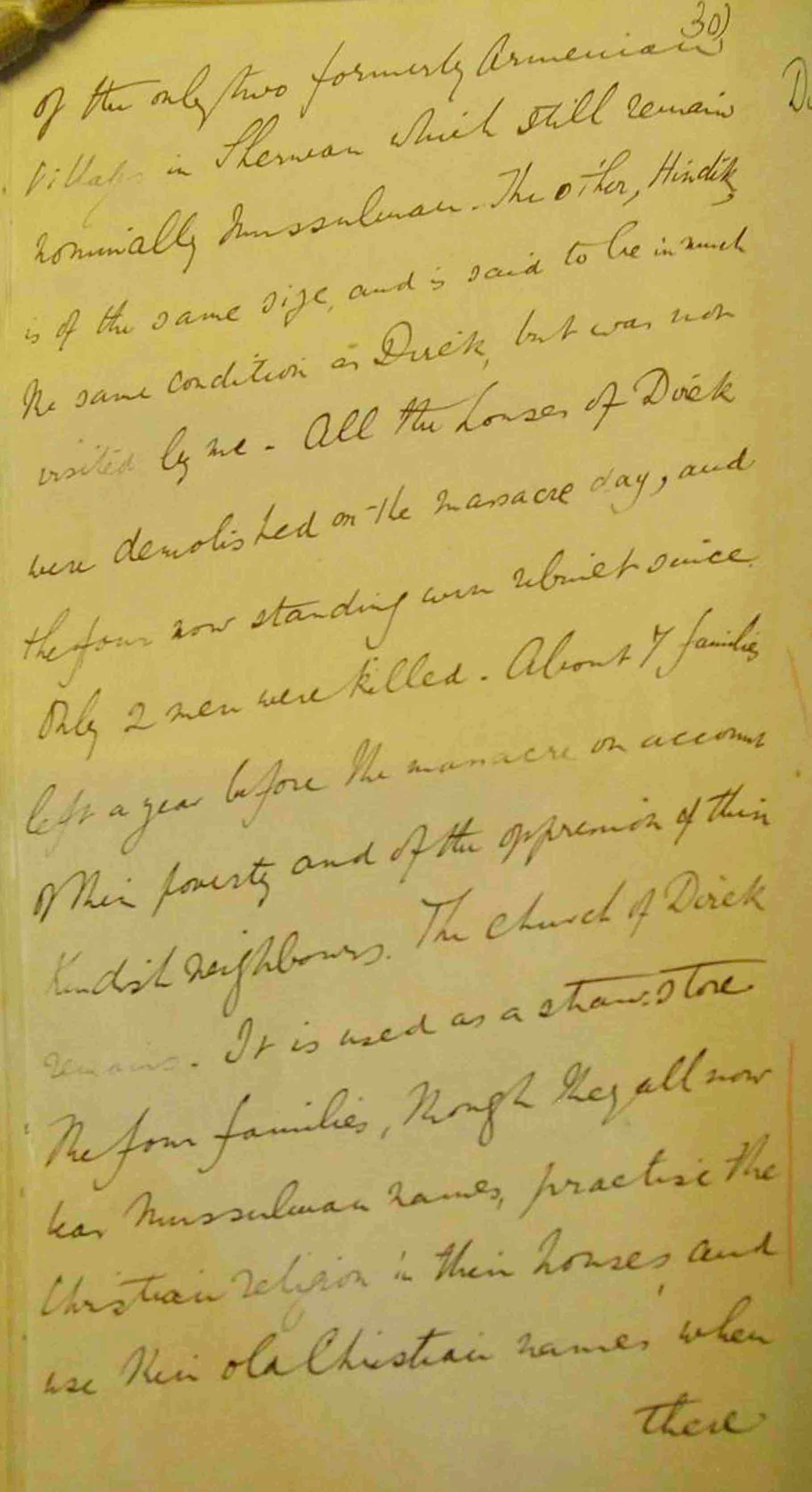

We next travelled past just vine yards [?] into the rich little plain of Kormuz with its fields of cotton rice and cotton dominated by two ruined Kurdish castles. On the side of the village of overlooking the plain from the Northeast we camped at the wretched little hamlet of Direk. Direk consists of four converted Armenian houses, one

[171v] of the only two formerly Armenian villages in Sherwan which still nominally Mussulman. The other, Hindik, is of the same size, and is said to be in much the same condition as Direk, but was not visited by me. All the houses of Direk were demolished on the massacre day, and the four now standing were rebuilt since. Only 2 men were killed. About 7 families left a year before the massacre on account of their poverty and of the oppression of their Kurdish neighbours. The church of Direk remains. It is used a straw store. The four families, though they all now have Mussulman names, practise the Christian religion in their houses and use their old Christian names when

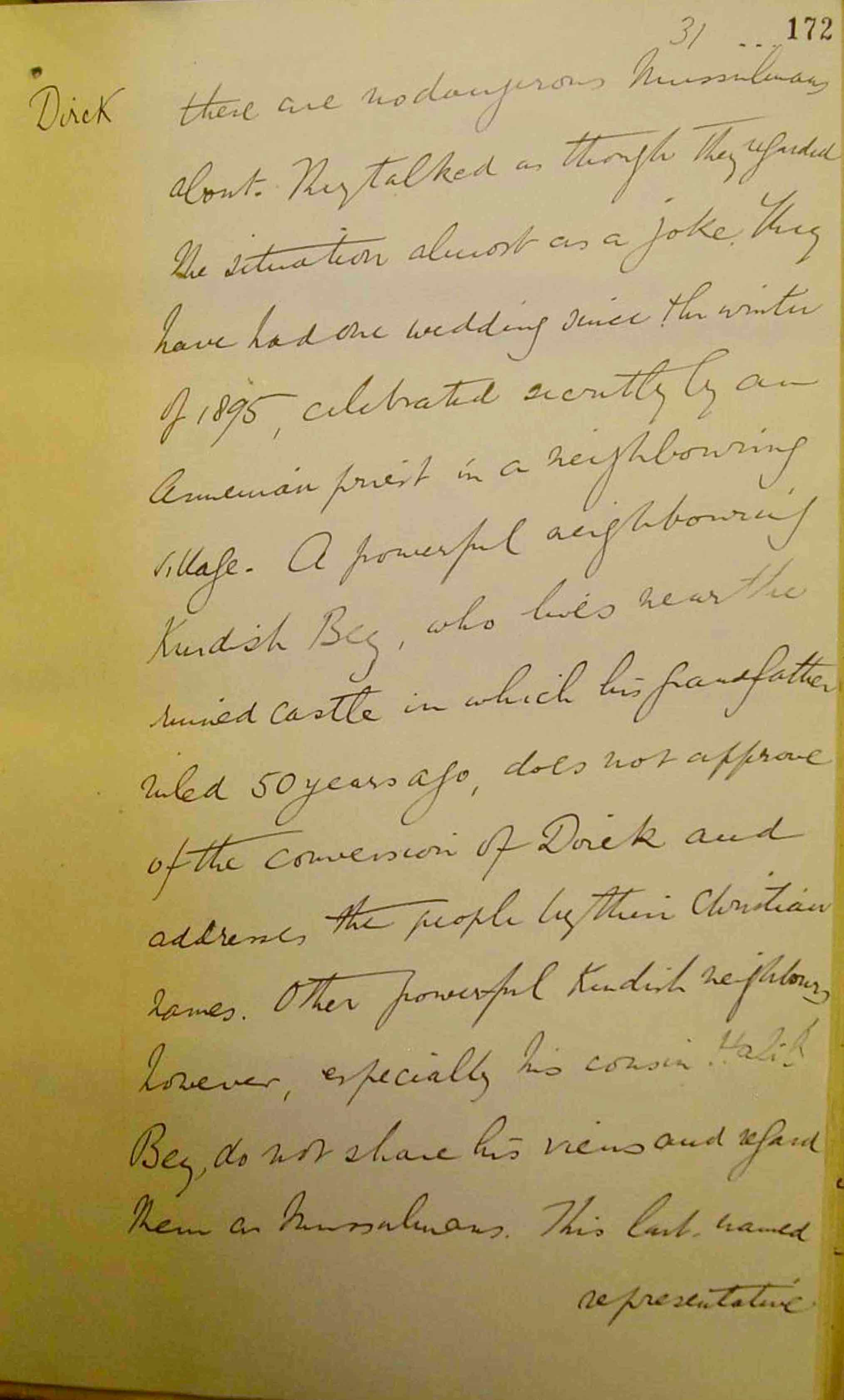

[172] there are no dangerous Mussulmans around. They talked as though they regarded the situation almost as a joke. They have had one wedding since the winter of 1895, celebrated secretly by an Armenian priest in a neighbouring village. A powerful neighbouring Kurdish Bey, who lives near the ruined castle in which his grandfather ruled 50 years ago, does not approve of the conversion of Direk and addresses the people by their Christian names. Other powerful Kurdish neighbours however, especially his cousin, Halil Bey, do not share his views and regard them as Mussulmans. This last named

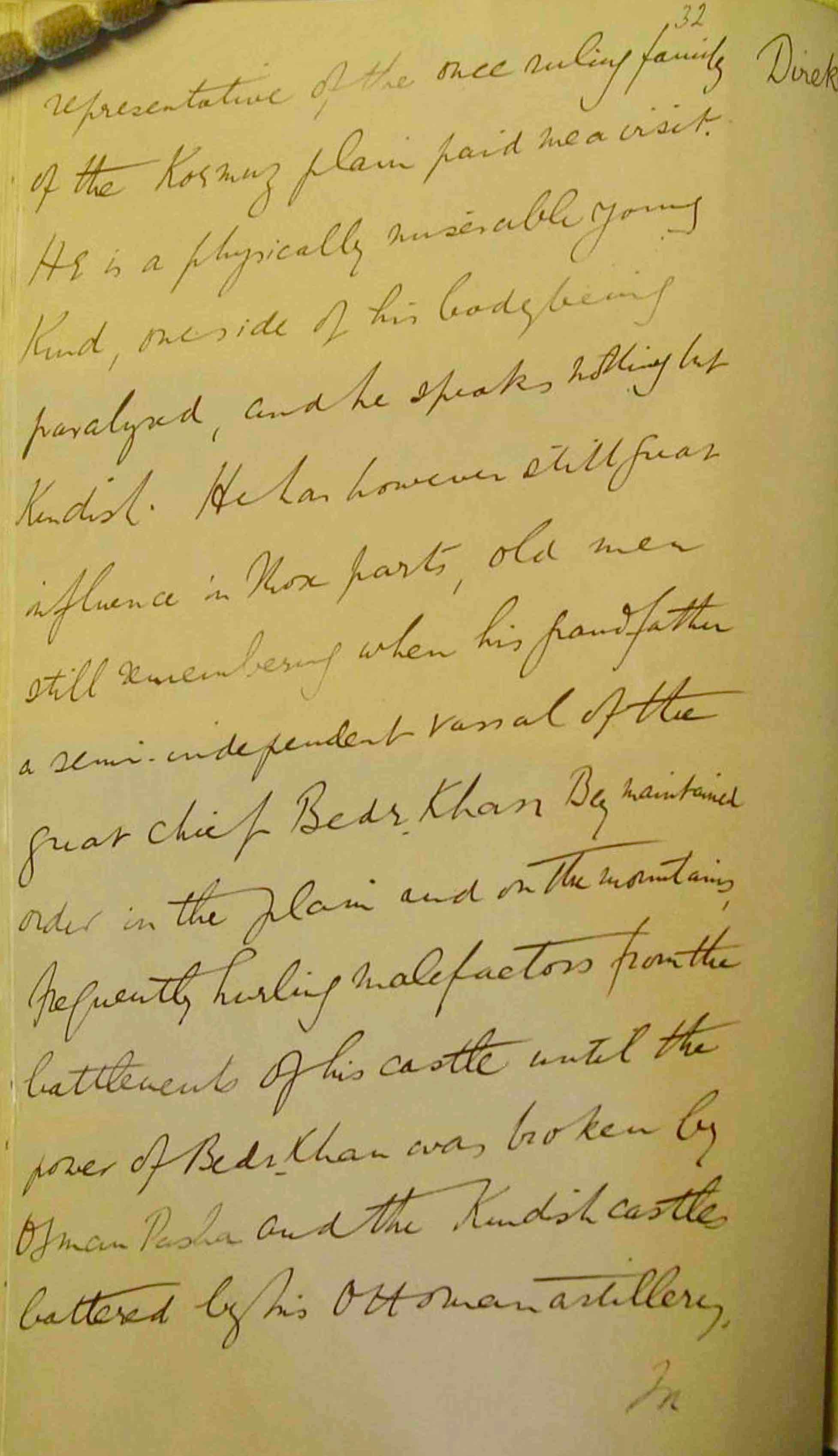

[172v] representative of the once ruling family of the Kormuz plain paid me a visit. He is a physically miserable young Kurd, one side of his body being paralysed, and he speaks nothing but Kurdish. He has however still great influence in this parts, old men still remember when his grandfather, a semi-independent vassal of the great chief Bedr Khan Beg, maintained order in the plain and the mountains frequently hurling malefactors from the battlements of his castle until the power of Beds Khan was broken by Osman Pasha and the Kurdish castles battered by his Ottoman artillery.

[173]

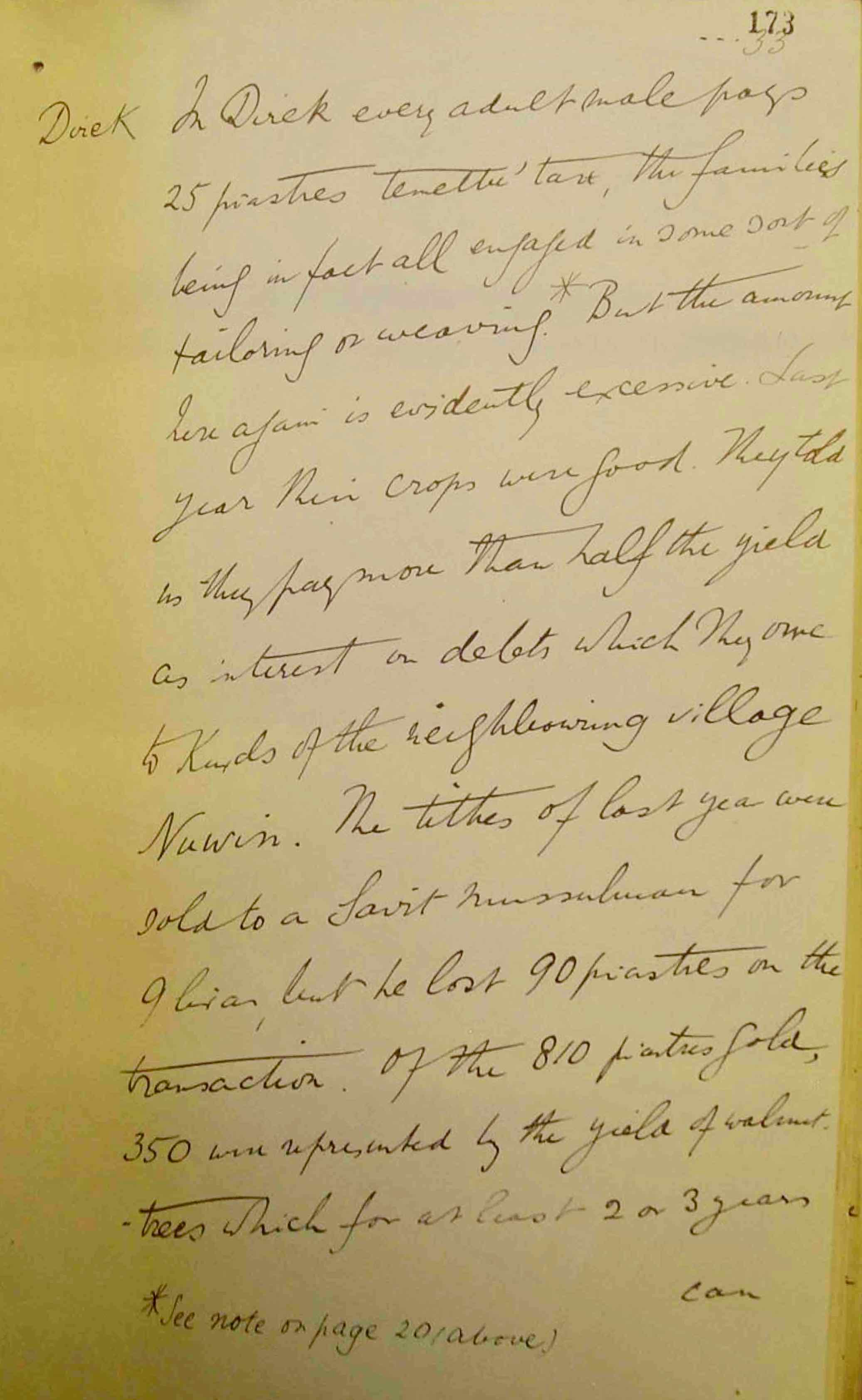

In Direk every adult male pays 25 piasters temettu’ tax, the families being in fact all engaged in some sort of tailoring or weaving. But the amount here again is evidently excessive. Last year their crops were good. They told me they pay more than half the yield as interest in debts which they owe to Kurds of the neighbouring village Nuwin. The tithes of last year were sold to a Sairt Mussulman for 9 liras, but he lost 90 piasters on the transaction. Of the 810 piasters gold, 350 were represented by the yield of walnut trees which for at least 2 or 3 years

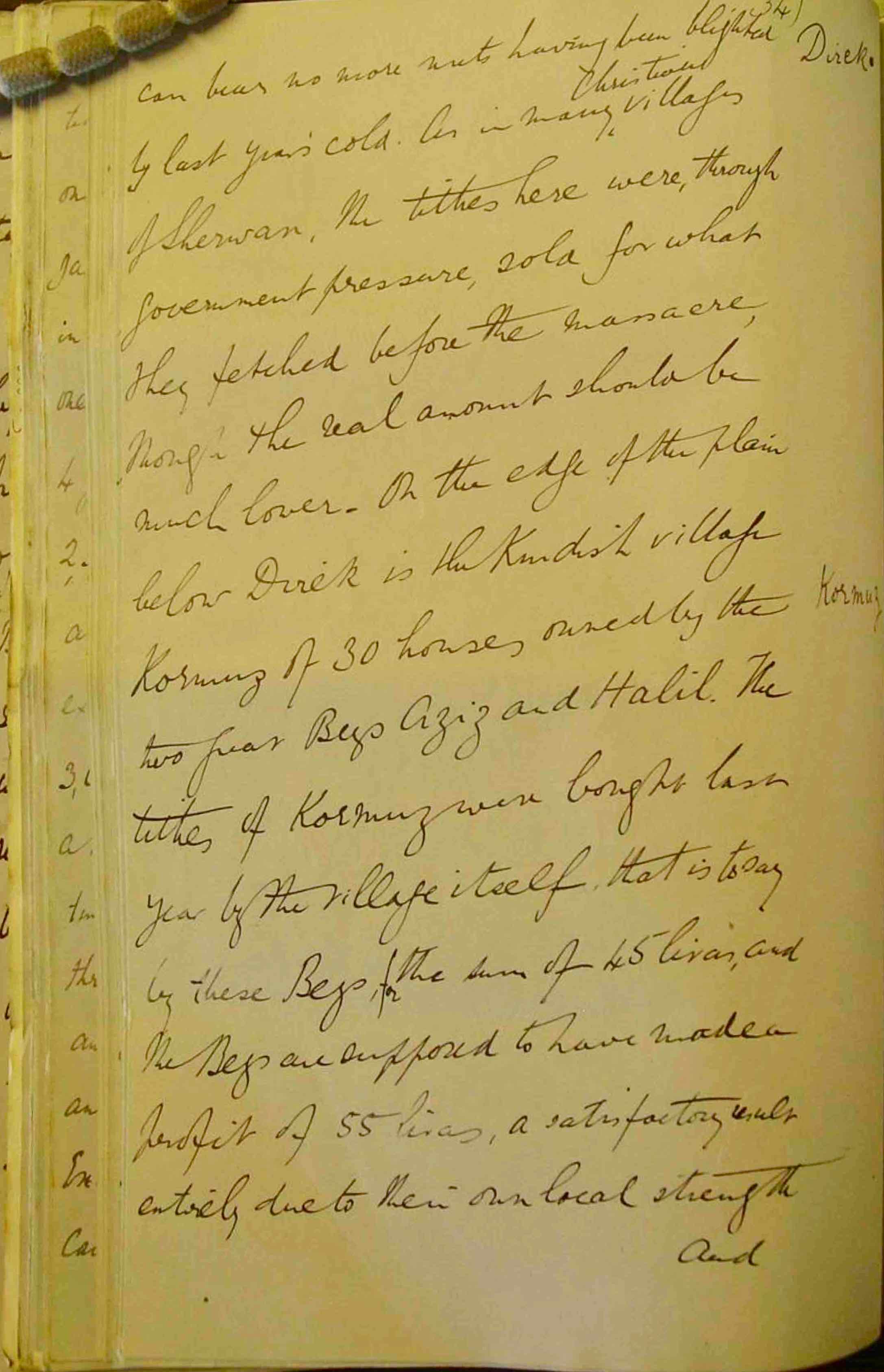

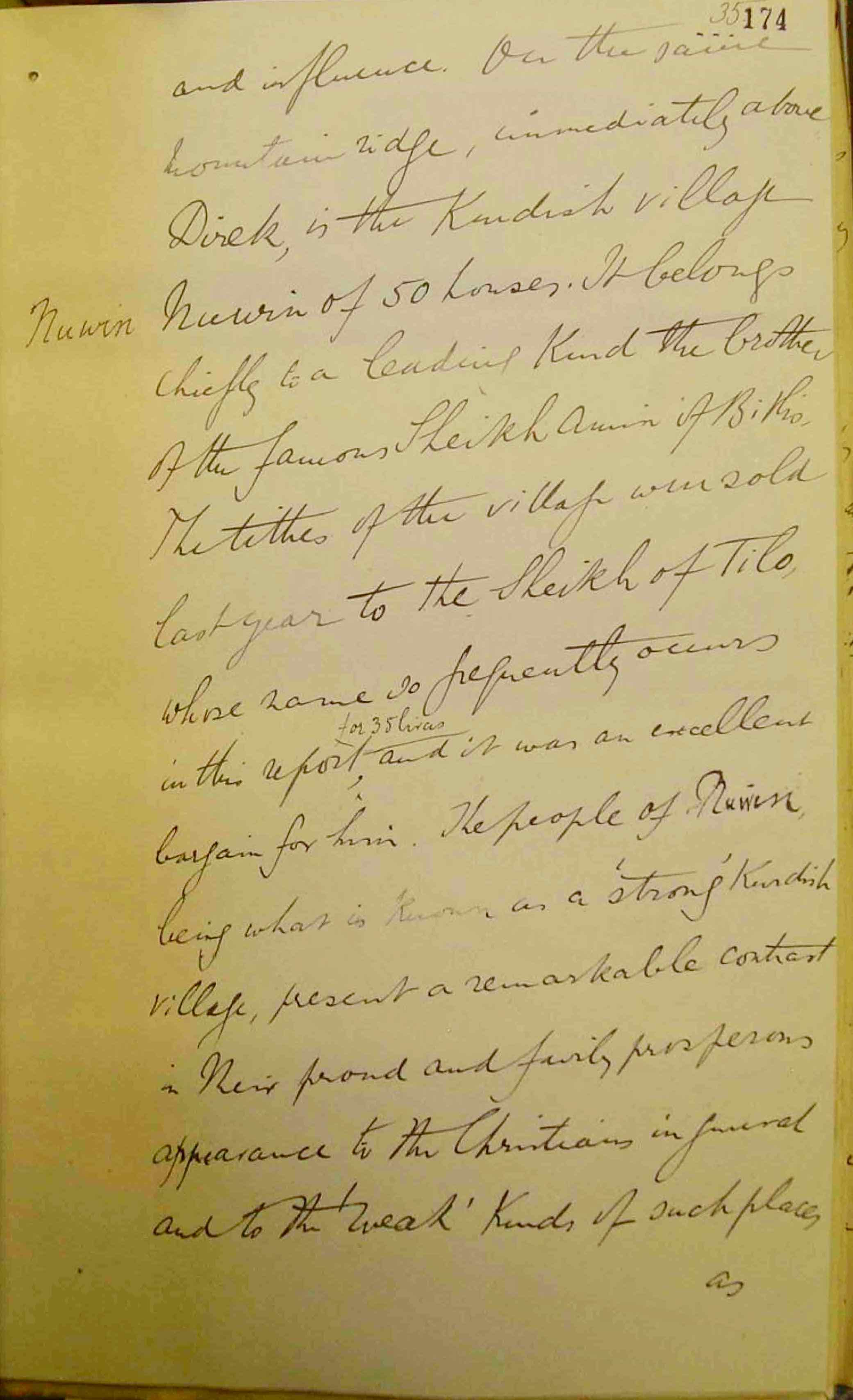

[174] and influence. On the same mountain ridge, immediately above Direk, is the Kurdish village Nuwin of 50 houses. It belongs chiefly to a leading Kurd, the brother of the famous Sheikh Amin of Bitlis. The tithes of the village were sold last year to the Sheikh of Tilo, whose name so frequently occurs in this report, for 35 liras, and it was an excellent bargain for him. The people of Nuwin, being what is known as a strong Kurdish village, present a remarkable contrast in their proud and fairly prosperous appearance to the Christians in general and to the ‘weak’ Kurds of such places

[173v] can bear no more nuts having been blighted by last year’s cold. As in many Christian villages of Sherwan, the tithes here were, through Government pressure, sold for what they fetched before the massacre, though the real amount should be much lower. On the edge of the plain below Direk is the Kurdish village Kormuz of 30 houses, owned by the two … Beys Aziz and Halil. The tithes of Kormuz. The tithes of Kormuz were bought last year by the village itself. That is to say by these Beys, for the sum of 45 liras, and the Beys are supposed to have made a profit of 55 liras, a satisfactory result entirely due to their own local strength

Kormuz → İncekaya village (Şirvan district, Siirt province)

Nuwin → Tatlıpayam village (Şirvan district, Siirt province)

pages 165v - 174