19th century sources

website of Jelle Verheij, historian

home | publications | pictures | historical pictures | travel snap shots | monuments | 19th century sources | research tools | links | contact

Report on a Journey in the Cazas Sherwan, Sairt, and Aroh May and June 1898

(by J.H. Monahan, British Vice-Consul in Bitlis)

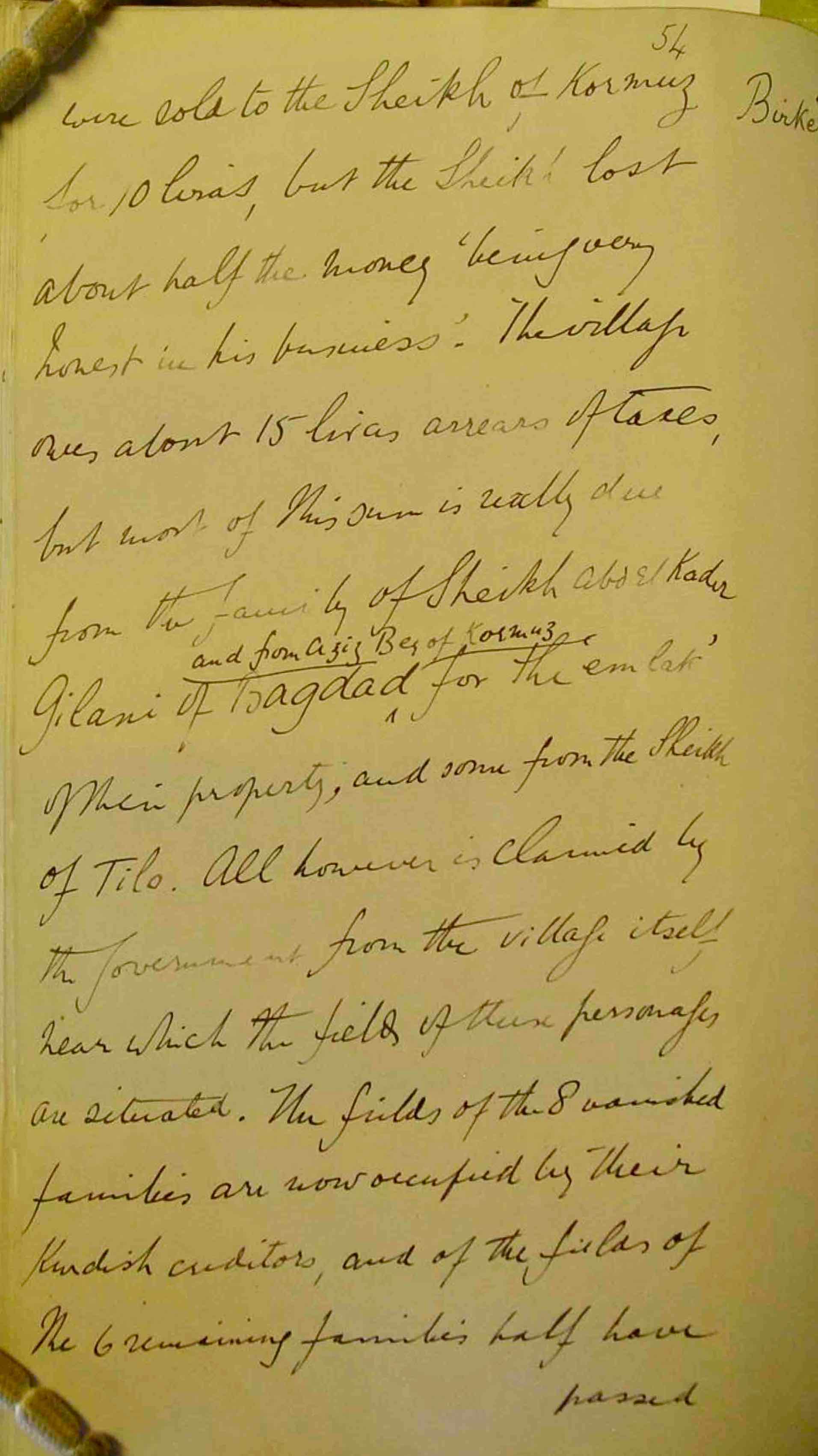

[183v] were sold to the Sheikh of Kormuz for 10 liras, but the Sheikh lost about half the money being very honest in his business. The village has about 15 liras arrears of taxes, bus most of this sum is really due from the family of Sheikh And el Kadir Gilani of Baghdad and from Aziz Beg of Kormuz, for the ‘emlak’ of their property, and some from the Sheikh of Tilo. All however is claimed by the Government from the village itself near which the fields of these personages are situated. The fields of the 8 vanished families are now occupied by their Kurdish creditors, and of the fields of the 6 remaining families half have

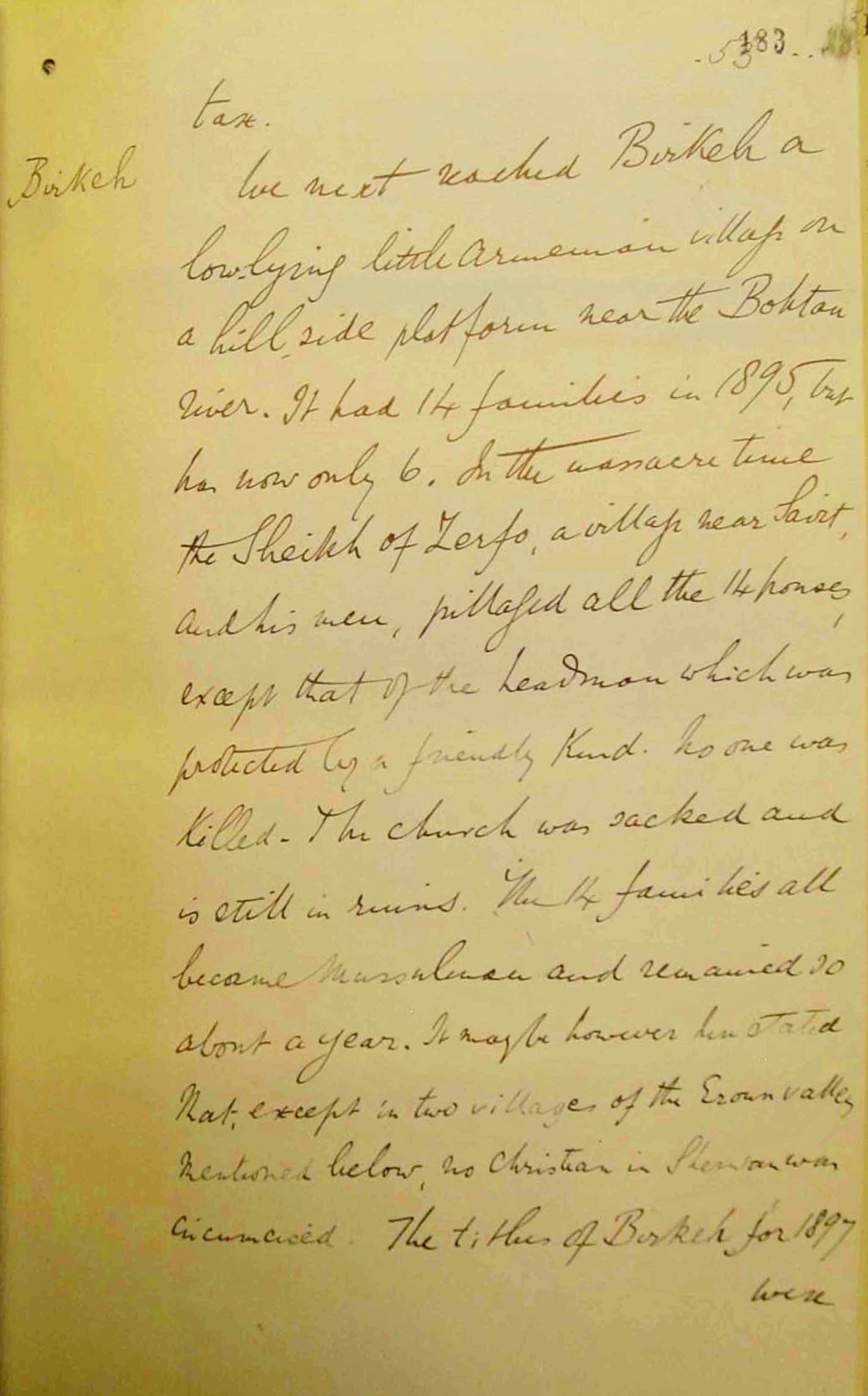

[183] tax.

We next reached Birkeh, a low-lying little Armenian village on a hill side platform near the Bohtan river. It had 14 families in 1895, but now only 6. In the massacre time the Sheikh of Zerfo, a village near Sairt, and his men, pillaged all the 14 houses, except that of the headmen which was protected by a friendly Kurd. No one was killed. The church was sacked and is still in ruins. The 14 families all became Mussulman and remained so about a year. It may be however … stated that, except in two villages of the Eroun valley mentioned below, no Christian in Sherwan was circumcised. The tithes of Berkeh for 1897

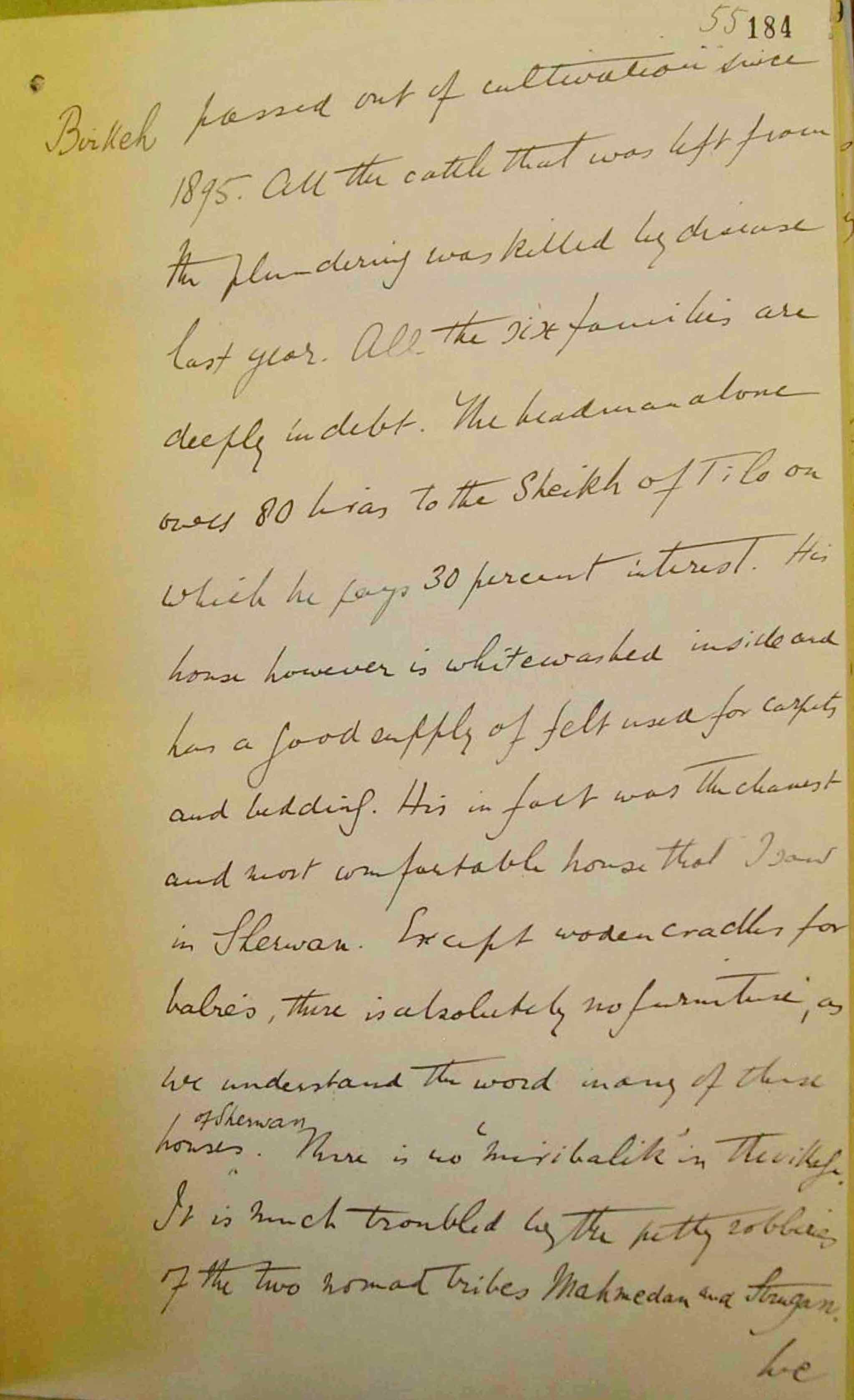

[184] passed out of cultivation since 1895. All the cattle that was left from from the plundering was killed by disease last year. All the six families are deeply in debt. The headman alone owes 80 liras to the Sheikh of Tilo on which he pays 30 percent interest. His house however is whitewashed inside and has a good supply of felt used for carpets and bedding. His in fact was the cleanest and most comfortable house that I saw in Sherwan. Except wooden cradles for babies, there is absolutely no furniture, as we understand the word in any of these houses of Sherwan. There is no ‘miribalik’ in the village. It is much troubled by the petty robberies of the two nomad tribes Mahmedan and Strugan.

[184v]

We saw a small detachment of about 10 families of the Strugan pass near the village on the way to their summer pasturages, the men armed with ancient guns and the women as usual laden like beasts of burden. Our presence with zaptiés had the satisfactory effect of keeping them them out of the village which they would otherwise have passed through.

From Birkeh we proceeded about 1 hours’ journey in to the caza of Aroh on the southern side of the Bohtan River which we crossed by what had once been a fine stone bridge but is now spanned by rough planks covered with twigs and and mud.

Aroh is a large caza, considerable larger I think than Sherwan, but very thinly

[185] populated and even a little more barbarous. The official figures of 5 years ago are 14,489 Mussulmans to 2,264 Christians, 1,668 of the latter being Armenians and the rest ‘Chaldeans’, that is Syrians or Jacobites who have joined the Roman Catholic Church. The only Armenians are in the chief town & village Deh where they number 260 families or about 1,560 souls and in one small village; so the official figures may perhaps be nearly correct for the present year. The ‘Chaldean’ villages seem to have been unmolested in 1895, but the Christians of Deh and the three Armenian villages were thoroughly plundered. Wild boars abound in Aroh.

The first village we came to was the Kurdish village Boshi (120 houses) overlooking

[185v] the Bohtan river from a height of about 1,000 feet. There was no one in the village except an old man, a woman and a boy, nor any animals except one or two mules. Our two gendarmes tried to impress upon us that this was the regular state of things and that it was the custom for the people to leave their village in this season and go to their tents on the summer pasture lands. We were however confidentially told by the old man that no such custom prevailed in the village, and that the people had in fact fled to the mountains to hide their appearance the day before. Towards evening people be a to come back with their small herds of oxen, and by nightfall

[186] the village was full. Behind the backs of the two gendarmes, these people unanimously corroborated the story of the old man, but when either of them was present the agreed with the story of the customary camping on the summer pasture lands, which the two gendarmes continued to repeat to us. Our gendarmes were very vigilant, and the people very shy of giving us information, so we heart little else about Boshi. We were told that the only European who had ever visited Boshi was the Russian Vice-Consul at Van who had come last year and had “written down” that is made maps of the whole country. In the night the Kurds entertained us with a comedy called the ‘dead wild beast”. A man, otherwise almost naked

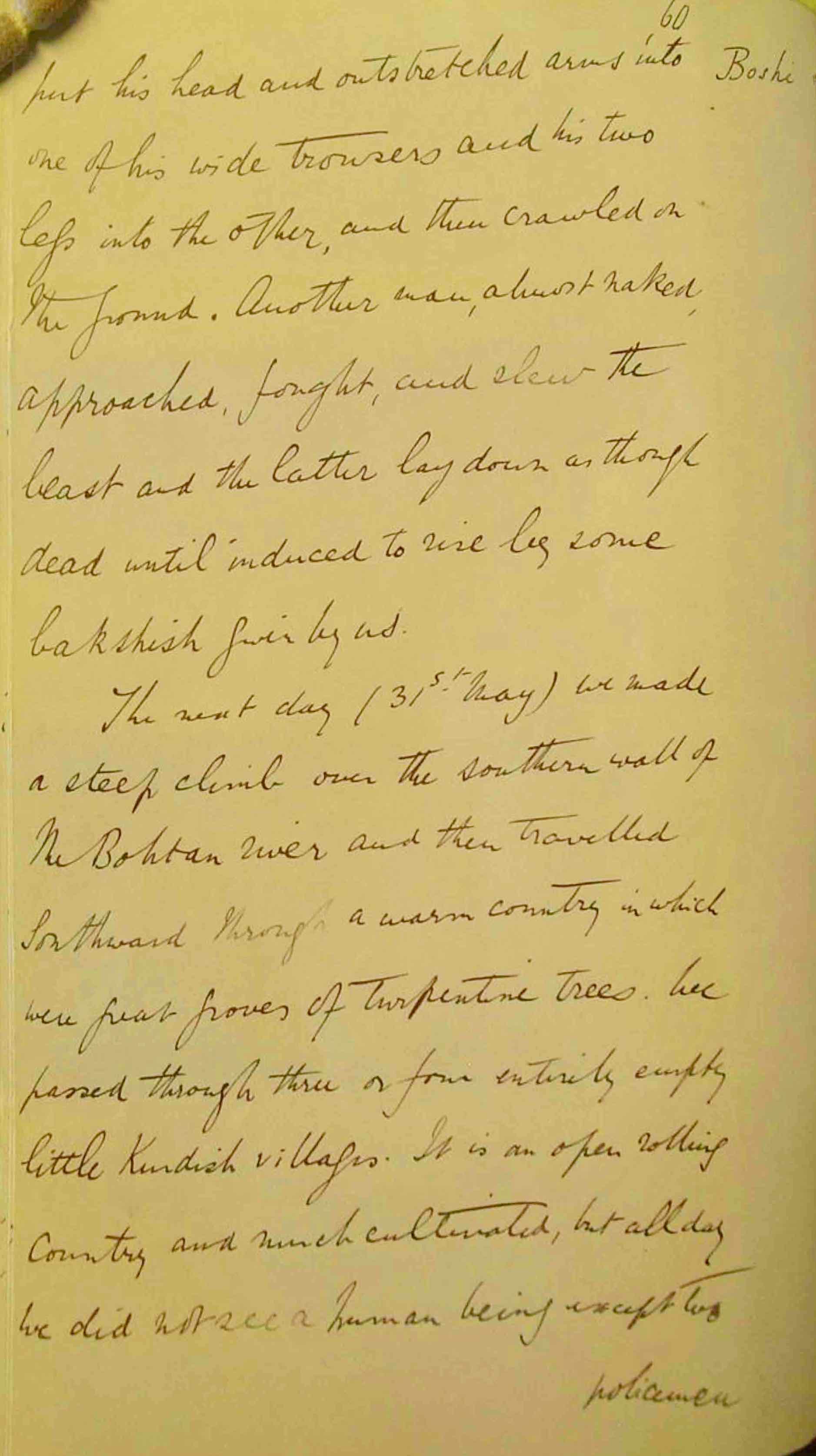

[186v] put his head and outstretched arms into one his wide trousers and his two legs in the other and the crawled on the ground. Another man, almost naked, approached, fought and slew the beast and the latter lay down as though dead until induced to rise by some baksheesh given by us.

The next day (31th May) we made a steep climb over the northern wall of the Bohtan river and then travelled southward through a warm country in which were great groves of turpentine trees. We passed through three or four entirely empty little Kurdish villages. Ir is an open rolling country and much cultivated, but all day we did not see a human being except the

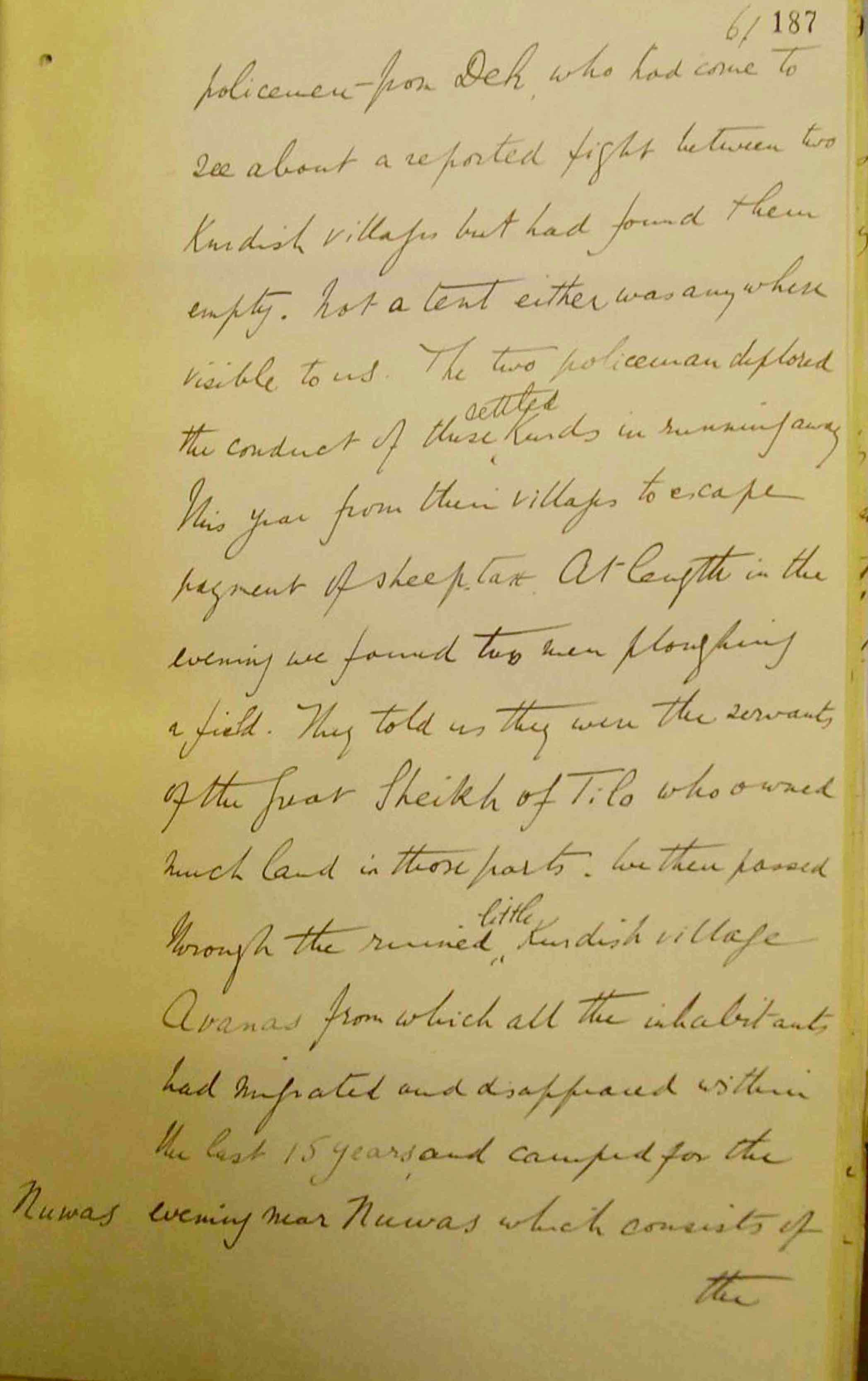

[187[ policemen from Deh, who had come to se about a reported fight between two Kurdish villages but had found them empty. Not a tent either was anywhere visible to us. The two policemen deplored the conduct of these settled Kurds in running away this year from their villages to escape payment of sheep tax. At length in the evening we found two men ploughing a field. They told us they were the servants of the Great Sheikh of Tilo, who owned much land in these parts. We then passed through the ruined, little Kurdish village Avanas from which all the inhabitants had migrated and disappeared within the last 15 years, and camped for the evening near Nuwas, which consists of

[187v] the house of one Suleiman Agha and three houses of his retainers. He and his men are well known as robbers of caravans on the Deh road, but he seemed a benevolent old gentleman and complained piteously of the terrible oppressive tax-collecting.

Two hours further to the South is Deh, the chief town of the Aroh caza. For about half of this distance there is a partly made road, the only one on the Aroh caza.

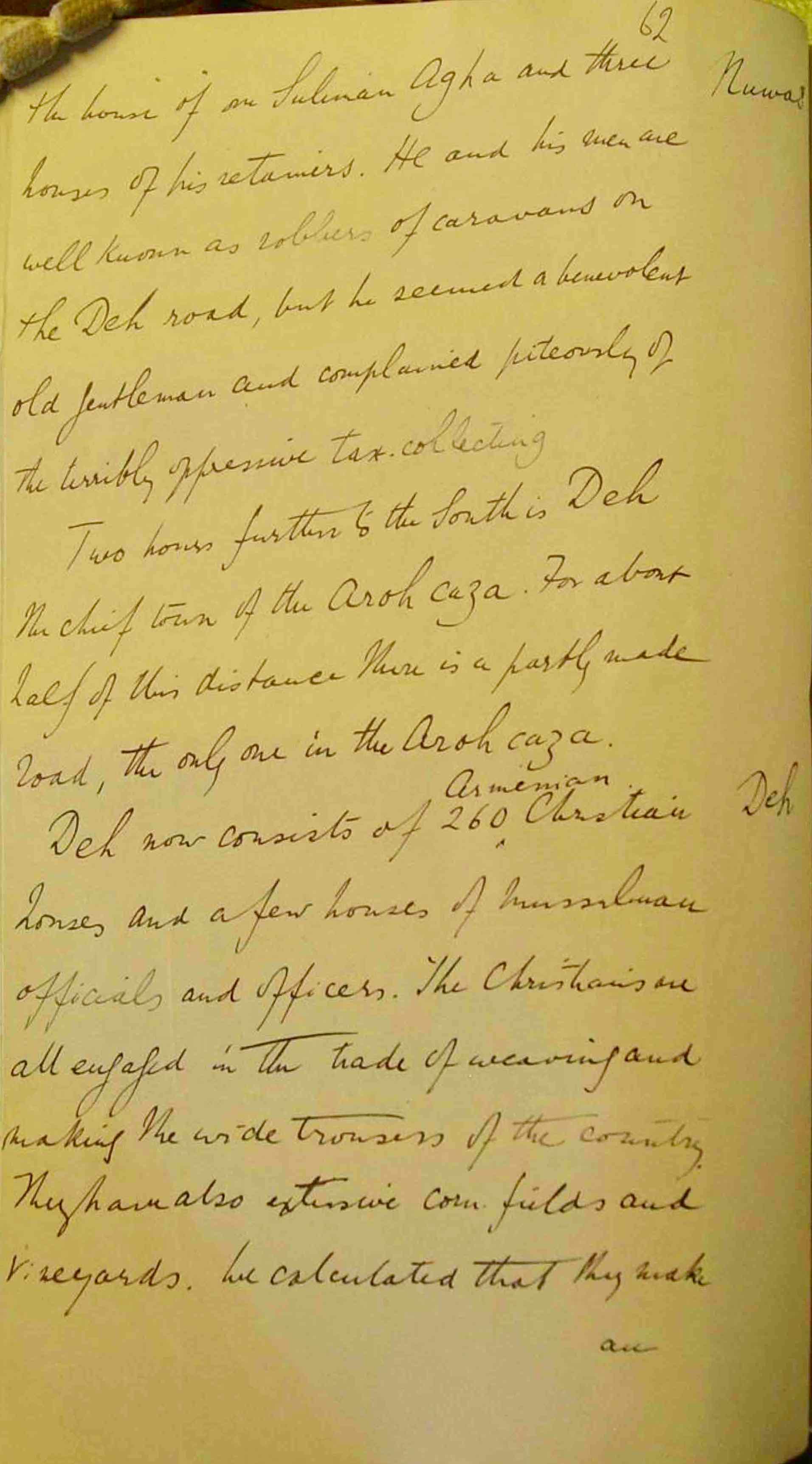

Deh now consists of 260 Armenian Christian houses, and a few houses of Mussulman officials and officers. The Christians are all engaged in the trade of weaving and making the wide trousers of the community. They have also extensive corn fields and vine yards. We calculated that they make

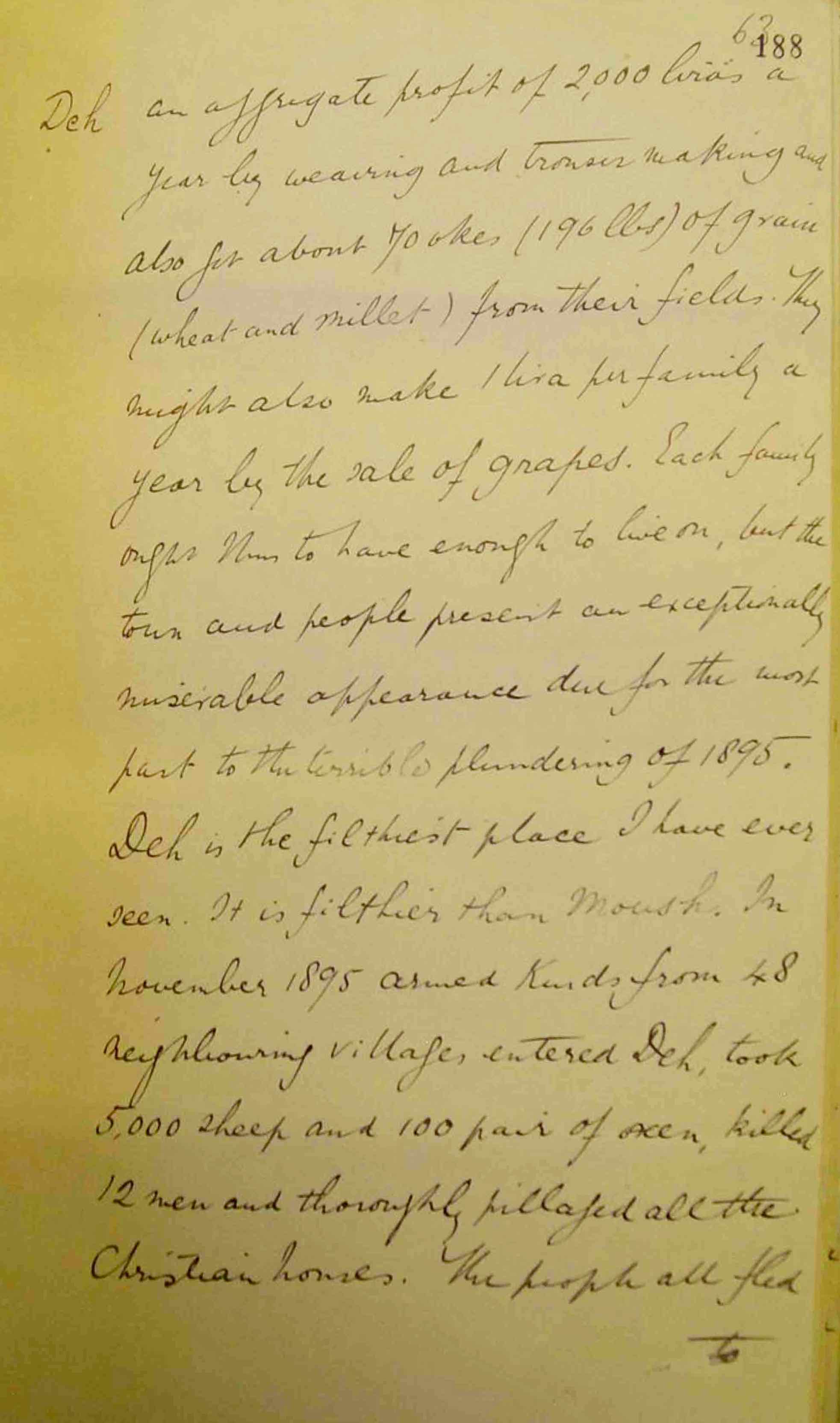

[188] an aggregate profit of 2,000 liras a year by weaving and trouser making and also for about 70 okes (196 lbs) of grain (wheat and millet) from their fields. They might also make 1 lira per family a year by the sale of grapes. Each family ought thus to have enough to live on, but the town and people present an exceptionally miserable appearance due for the most part to the terrible plundering of 1895. Deh is the filthiest place I have ever seen. It is filthier than Mush. In November 1895 armed Kurds from 48 neighbouring villages entered Deh, took 5,000 sheep and 100 pair of oxen, killed 12 men and thoroughly pillaged all the Christian houses. The people all fled

[188v] to the mountains, but the captain of Deh gendarmerie, Ferhad Agha, who is still in Deh, invited them back saying that if they became Mussulmans they would be safe. After one or two nights on the mountains they all came back and declared themselves Mussulmans to the officials. But only ten days later, as the chief Christians of Deh assured us, they returned to the profession of Christianity without any opposition offered by the Government or by Kurds. It seems to have been thought that they should remain Christians and practise the necessary art of trouser making. They have no sheep now and few oxen. They have paid all their taxes up to date including military

[189] exemption tax which latter clearly should not have been levied for them. They complain much of Ferhad Agha and some other gendarmerie officers who at the time of tax-collecting advance them “selef” loans (see above) on the security of trousers to be afterwards made, which loans are at the rate of 60 percent per annum. They complain of Ferhad Agha, Sheikh Halid the ‘juge d’instruction’, and Kazim Effendi , the chief clerk of the local tribunal, who levy forage for their many horses without payment. Ferhad Agha alone has six horses. Since the time of the plundering, the whole of the Christian population is deeply, and it would seem hopelessly, in debt. The only school has remained closed

[189v] since that time, and the school building is falling into ruins. There are two priests and the Christian religion is truly practised. The Miranli nomads coming from the south were not expected for about 3 weeks. They are the most formidable of all the nomad tribes that pass every year into or through the Bitlis Vilayet. Most of the Miranlis go on into the Van Vilayet. Being at feud with a tribe of settled Kurds in the Eastern mountains of Aroh, they have for the last three years passed through the Deh district doing much damage to the crops. A local zaptié of Deh informed me that these Miranlis had for the last two years been accompanied in each migration by a battalion of regular soldiers. But,

[190] he added, the soldiers did nothing to prevent damaging of crops and plundering, but only stopped the fighting between the Miranlis and their Kurdish enemies. The local authorities took the precaution of keeping 5 of the chief Christians in prison on some pretext for the first night of our stay at Deh, and our camp was carefully watched by police, so were not able to get much information. Two petitions, of which I give a summary translation, were however secretly conveyed to us on the following night.

Translation. Petition from the Christians of Deh (no date, presented June 2nd, 1898)

“We wish to tell you of our miserable plight since the date of the Firman.

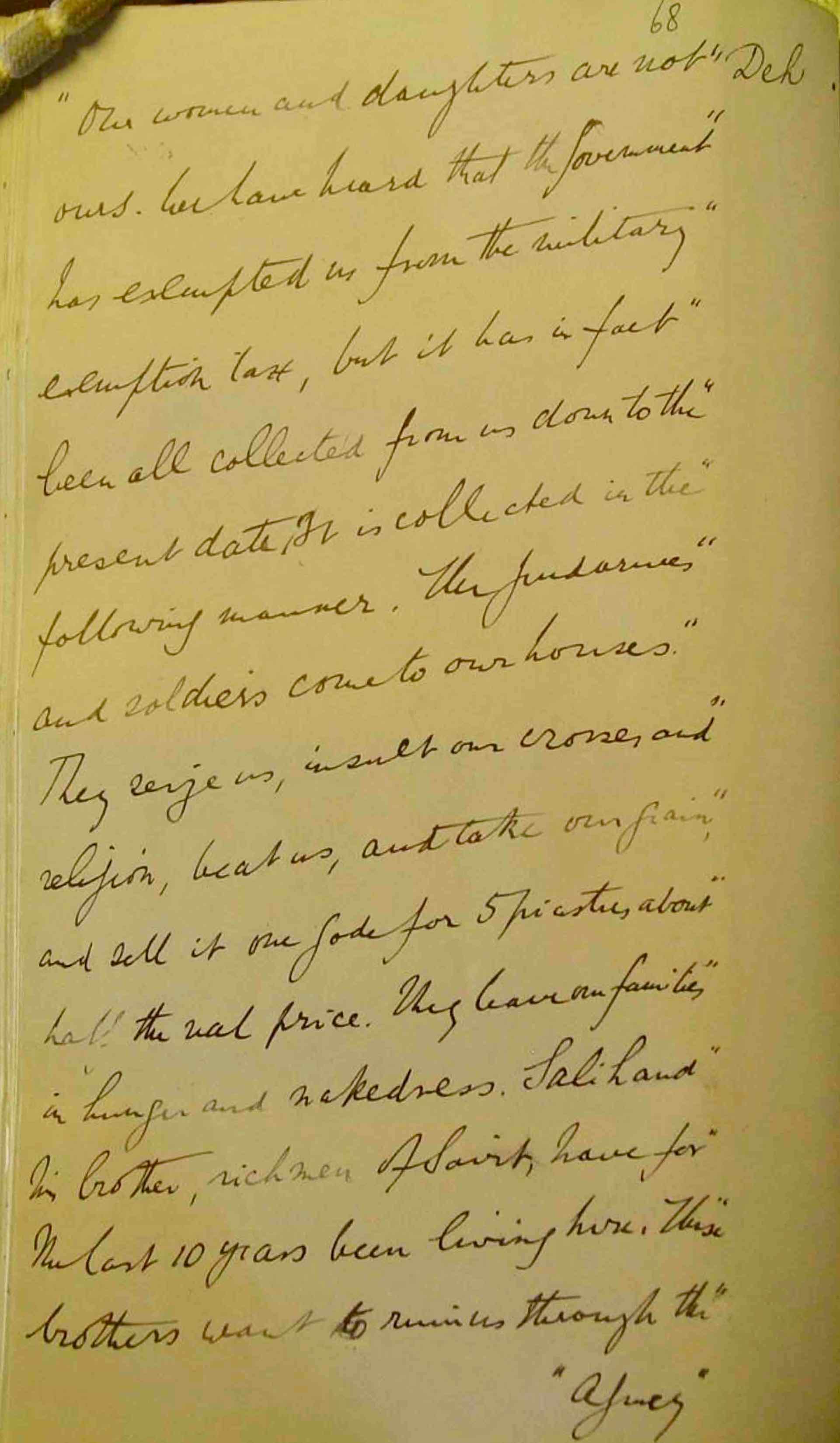

[190v] Our woman and daughters are not ours. We have heard that the Government has exempted us from the military exemption tax, but it has in fact been all collected from our down to the present date. It is collected in the following manner. The gendarmes and soldiers come to our houses. They … us, insult our crosses and religion, beat us, and take our grain and sell it one .. for 5 piasters about half the price. They leave our families in hunger and nakedness. Salih and his brother, rich men of Sairt, have for the last 10 years been living here. These brothers want to ruin us through the

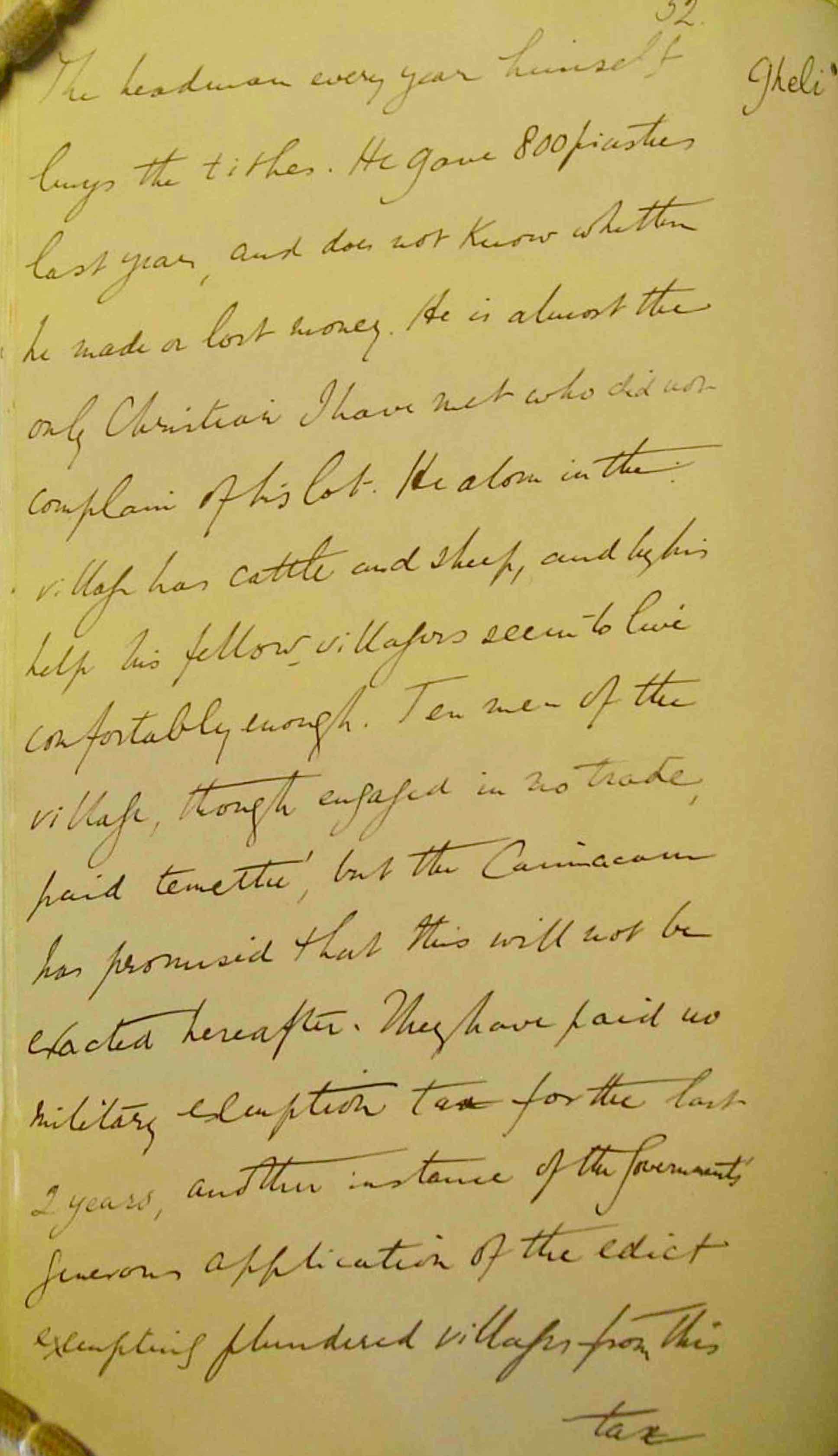

[182v] The headman every year himself buys the tithes. he gave 800 piasters last year, and does not know whether he made or lost money. He is almost the only Christian I have met who did not complain of his lot. He alone in the village has cattle and sheep, and by his help his fellow villagers seem to live comfortably enough. Ten men of the village, though engaged in no trade, paid temettu’, but the Caimacam has promised that the will not exacted hereafter. They have paid no military exemption tax for the last 2 years, another instance of the Government’s generous application of the edict exempting plundered villages from this

Boshi → Meydandere (village in Siirt central district, Siirt province)

Avanas → not identified

pages 182v - 190v